周易现代解读 中华书局出品

¥14.70

《周易现代解读》是著名哲学家、易学大家余敦康所撰对《周易》进行现代解读的入门性普及读物,目的在于站在现代人的角度,适应现代人的需要,把艰深晦涩的《周易》变为人人都能读懂的书,把易学的智慧变为人人都能掌握的精神财富。作者认为易学都是时代的产物,明体达用的精神是一脉相承的,因而如何在现代的历史条件下继承这种明体以达用的精神,把易学的智慧运用于现代人的伦常日用,也许是促使易学切合时代需要由传统向现代转型的一种选择。基于这种考量,作者力求改变过去所奉行的学院派的研究方式,面向社会大众,对通行的经传合一的《周易》文本进行逐字逐句的训释,扫除文言与白话的语言障碍,沟通传统与现代的时空距离,凸显文本内在的哲理智慧,尽可能地在通俗易懂方面下工夫,以让当前读者易于理解易于把握。

宽容

¥14.63

在与世无争的山谷里,有一片世外桃源。

现代信仰学导引

¥14.60

信仰之于我们这个时代的重要性已经不言而喻。在新时代的召唤下,研究、构建现代信仰学,已成为有重大理论和现实意义的工作。

王安石全集(第一册):易解 礼记发明 字说

¥14.53

《王安石全集(**册易解礼记发明字说)(精)》是《王安石全集》的**部分,包含王安石所自撰的经学*作。作为引领北宋中后期学术的“新学” 的创始者和重要代表人物,王安石的经学*作,曾引领一代学术,但由于种种原因,这部分*作大多已散佚。本书所收录的各种*作,均是整理者遍览群书后辑得的珍贵文献。全书对于还原王安石经学*作的原貌,以至对宋代经学史、思想史的研究均具有重要意义。

中国哲学十讲 中华书局出品

¥14.46

本书先从整体上对中西方哲学的几个重要发展阶段和代表性思想家加以对比,而后选取了中国哲学*重要的九个流派思想,深入各派哲学文本,分别作详尽的评述,其援西入中的研究进路和精辟观点在同时期的中国哲学著作中可谓独树一帜。

易学今昔 中华书局出品

¥14.46

余敦康所*的《易学今昔》对易学史的发展脉络以及现代中国哲学家对易道的探索的梳理,凸显出作为中国古代群经之首的《周易》价值。而对《周易》的思想精髓与价值理想、《周易》与中国文化、政治文化、伦理思想的关系的探讨,以及易学对于现代人的生活智慧、易学的管理思想的精到讨论也使易学本身的日用性得以道破,充分体现出《周易》的现代价值有多重要。

《弟子规》读本(大众儒学经典)

¥14.46

《弟子规》是清朝以来有广泛影响的蒙学读物,与《三字经》、《千字文》等相配合,在推动民间礼义文明和儿童德育事业中发挥了重要作用。《弟子规》的内容来源于《论语》中的“弟子入则孝,出则弟,谨而信,泛爱众,而亲仁,行有余力,则以学文”,这段话可以视为孔子的教学大纲。《弟子规》包括了孝悌、忠信、仁爱、恭谨等儒家修身功夫,内容具体详尽,紧扣人伦日用,为现今国民教育中*为紧缺的儿童礼仪修养教材。 《〈弟子规〉读本》包括原文、注释、译文、解读等部分,准确阐发了《弟子规》的义理,以及它对于当代青少年教育的现实意义,对儿童修身做人具有重要参考价值。

孟子与滕文公、告子

¥14.40

本书分为两部分:《孟子与滕文公》、《孟子与告子》。在这本书里,南先生对于中国历史上对人性善恶的辩论做了令人信服的裁断;对于中国传统文化观念中人应有的立身、处世精神,结合历史上正反两面的实例,行阐发。读来意味深长,令人警醒怵惕。

老祖宗不能丢:学习和掌握马克思主义十讲

¥14.40

20世纪90年代初期,针对一些企图割裂中国改革开放同马列主义、*思想关系的错误思潮,邓小平明确提出“老祖宗不能丢”的思想主张,旗帜鲜明地表达了要继承和发展马克思列宁主义、*思想,坚定地走中国特色社会主义道路的立场。 20多年过去了,中国已步入全面深化改革的历史新时期,站在新的历史起点上,学习和研究邓小平“老祖宗不能丢”的思想主张在今天依然具有重要意义。老祖宗不能丢,就是指马克思列宁主义、*思想不能丢,就是指他们所创立的哲学世界观方法论不能丢,同时要处理好历史与当代、继承与发展的关系。本着这一精神,本书就马克思主义的创立和发展脉络、马克思主义中国化的理论体系、马克思主义军事理论的创立及其历史作用、学习和研究马克思主义经典著作的方法等十个重要问题进行相关阐释和解读,在编写中力争做到既全面地尊重历史,又有重点阐述历史,将马克思主义创立和发展的历史、马克思主义中国化的历史讲清楚。

孟子诵读本(不提供光盘内容) 中华书局出品

¥14.40

北京阳光润智文化传播有限责任公司是中华书局推广经典教育的直属部门,依托中华书局丰富的作者资源,承续中华书局弘扬中华传统文化之夙愿,结合时代需求,整合媒体优势,努力实现传统文化在传播中的内容大众化、产品系列化、形式多样化。 目前以开展经典教育和经典培训为主,主要有高潮文化论坛,大众国学系列讲座策划,咨询和实施,经典文化图书策划和出版等三大文化板块业务。

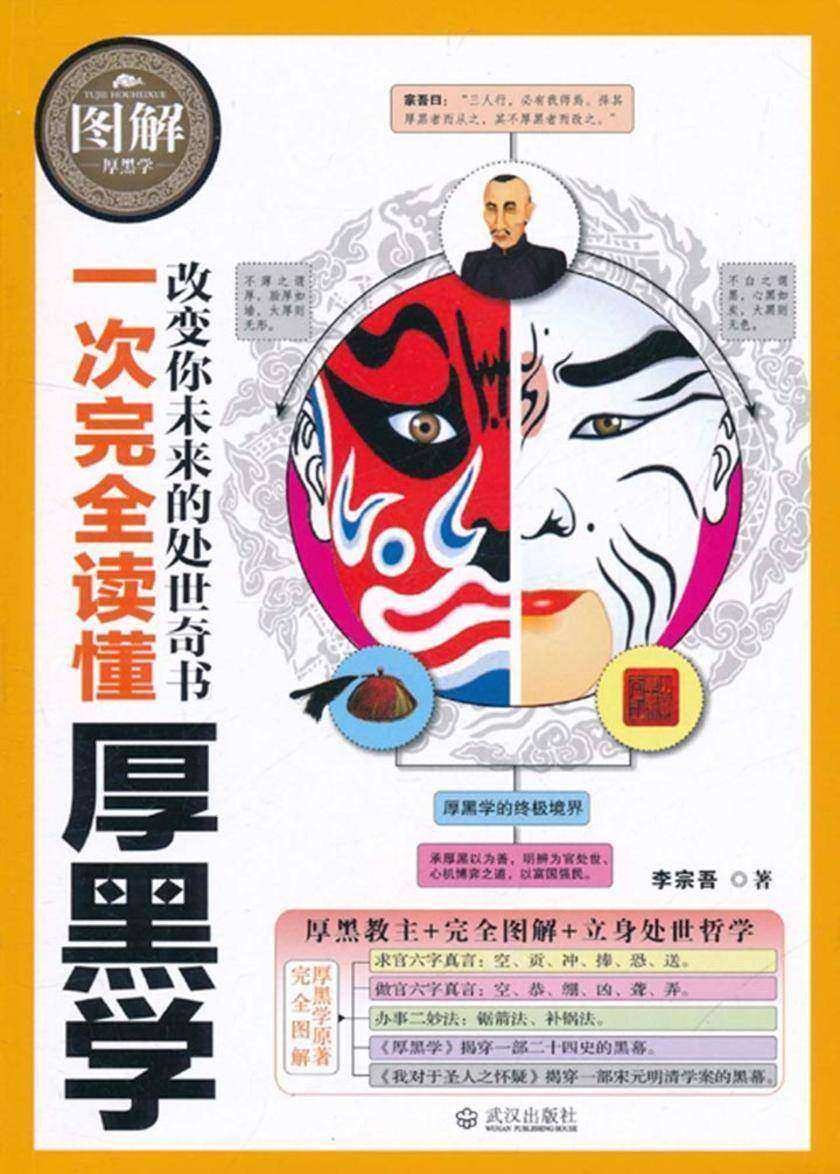

一次完全读懂厚黑学

¥14.40

厚黑学始源于我国文化史上极具争议性人物——“厚黑教主”李宗吾之手,以其冷眼阅尽世俗纷争、看透宦海沉浮之末奋笔而就,尽数古今成败背后所潜藏的“厚颜黑心”之说,诙谐辛辣,字字珠玑,被代代中国人奉为立身处世的旷世奇书。 《一次完全读懂厚黑学》收纳李宗吾大量的原著于一处,其中包括《厚黑学》、《厚黑学原理》、《厚黑丛话》、《厚黑别论》、《社会问题之商榷》、《中国学术之趋势》、《李宗吾自述》等,结合柏杨、南怀瑾、林语堂、许倬云等知名大家的精辟阐述,以图文并茂的形式详尽解读厚黑学的精妙神髓,全面、直观、速成的厚黑王道再现江湖。

双性人巴尔班

¥14.40

1868年,位于巴黎贫民区的医学院街,一间简陋、肮脏的阁楼,一名男性自杀身亡,旁边放着一本自传的手稿。1897年,这本自传以《阿莱克西纳·B的故事》为名,被一名法医学家编辑出版,人们这才发现了一位生活在黑暗之中的双性人的故事。这部双性人的自传以感情充沛的笔调讲述了一位年轻女孩经受的折磨和动荡,以及如何一步一步走向男性绝望的苦涩。1978年,在研究性史的过程中,福柯发现了这名“声名狼藉者”的生活。福柯把这部自传连同那些讨论“真实性别”所依据的医学和法律文件一同编辑出版,并附上一篇重要导读,阐释了双性人的身体如何成为话语/权力管控的对象。福柯借助“无确定性别”的快感概念,回应了19世纪以来医学和司法要求确定“真实性别”的做法。

中信国学大典·围炉夜话

¥14.40

《围炉夜话》提倡一种以儒家伦理观念为指引,更俭朴、更严整的生活态度,以求挽救他所认为自清中叶以来,日渐松散的社会……了解书的意义是步,下一步则是借由反思,摸索个体与社会的互动模式,寻出当代的出路与价值。

易经说什么

¥14.38

知道谜底,才能真正读懂《周易》 市面上常见的白话《周易》版本,似乎都能看懂。但一合上书,思考一下,就不知所云了。这些书中的绝大部分,不能说它们有问题,但可以说它们不适合普通读者自学。因为《周易》犹如一本谜语,其卦辞、爻辞犹如谜面。大多数的书只教你读懂谜面的文字,让你只知其然而不知其所以然。读者的智力是不能低估的!读者总是在读了白话解释后,还要在心里多问一些为什么。这一问,常常会把自己问糊涂,学不下去了! 《周易》这本“天书”的逻辑结构很复杂,解读的书汗牛充栋,各执一词又互相攻讦,欲言又止又遮遮掩掩,让人如入云里雾里。本书作者从30岁左右研究易学,至今已有20年。在本书中,他站在教师的角度,将自己在四川大学开授《周易》课程的讲记整理成书,十分适合年轻人自学。打开本书,你可以绕开陷阱,直抵《周易》的“正门”。

中国道教发展史略述

¥14.30

本文共分为八章,皆以道教发展史为中心。因欲说明道教学术之本原,故首先简述周、秦以前儒道等学并不分家之要。其次,略述周末学术分家,神仙方伎与老、庄等道家思想混合,为汉末以来道教成长之原因。复次,引述魏、晋、南北朝以后至于现代道教之发展,及与道家不可或分之微妙关系。虽其内容本质,原为不一不异,但道家与道教学术思想之方向,毕竟有其严整之界限。唯因包罗牵涉太广,不能尽作详论,但择其大要,及其演变过程之一鳞片爪,俾读者籍此可以窥见概略,并以提供研究者知所手,抑亦由此而了解秉中国文化创立之道教为何事而已。至于道教与道家学术内容,以及旁门左道等流派演变,有关于中国社会问题者,皆未及言。挂一漏万,有待他日专书之补充。

五百年来王阳明

¥14.27

本书结合两千年来中华文明发展史,生动讲述了王阳明立功、立德、立言的传奇人生,讲述了王阳明在千磨万的人生困厄中创建心学的历程,系统梳理了知行合一大智慧,并展了卓有见地的阐发。

鬼谷子(大全集)

¥14.26

鬼谷子,战国时期著名的思想家、谋略家、兵家,是纵横家的鼻祖,姓王名诩。常入云梦山采药修道,因隐居清溪之鬼谷,故自称鬼谷先生。他长于修身养性,精于心理揣摩,、深明刚柔之势,通晓捭阖之术,独具通天之智。是先秦神秘的历史人物。由于他的出现,历史上才有了纵横家的深谋,兵家的锐利,法家的霸道,儒家的刚柔并济,道家的待机而动。他的弟子有兵家孙膑、庞涓;纵横家苏秦、张仪等。, 《鬼谷子》着重于实践的方法,具有极完整的领导统御、智谋策略体系。堪称“中国奇书”,它以谋略为主,兼通军事,也是我国历史上部在充分探索人的心理特征和心理活动规律的基础上,论述劝谏、建议、协商、谈判和一般交际技巧的书。它讲授了不少政治斗争权术,其中重要的是取宠术、制君术、交友术和制人术。“智用于众人之所不能知,而能用于众人乏所不能”,潜谋于无形,常胜于不争不费,此为《鬼谷子》之精髓所在。 对于这本《鬼谷子大全集》,古往今来,人们从不同的角度解读,著作车载斗量、浩如烟海。其中观点驳杂、引经据典、卷轶浩繁,今人阅读,十分不便。为了增强可读性和实用性,我们编辑了这本《鬼谷子大全集》。《鬼谷子大全集》分为《捭阖》《反应》《内捷》《抵巇》《飞箝》《忤合》《揣》《摩》《权》《谋》《决》《符言》《本经阴符七术》《持枢》《中经》十五篇。前面四篇以权谋策略为主,中间八篇以言辩游说为重点,后面三篇则以修身养性、内心修炼为核心。本书对读者为人处世、邀游职场、搏击商海、闯荡人生都具有很高的实用价值,仔细研读它,您一定能从中获得处世的灵感,生活的谋略。 本书由张平、廖鹏编著。

菜根谭全鉴

¥14.06

《菜根谭》是一部论述修养、人生、处世、出世的语录集。该书融合了儒家的中庸思想、道家的无为思想和释家的出世思想,形成了一套独特的人生处世哲学,是一部有益于人们陶冶情操、磨炼意志、催人奋发向上的读物。 本书在原典的基础上,增加了精准的译文、生动的解读,联系当下诠释经典,可以更好地帮助人们塑造与人为善、内心安适、刚毅坚忍、处世恬淡的健康人格,探寻现实生活的智慧。

宽心:星云大师的人生幸福课

¥14.00

出世则有正见,世则有正行。星云大师以佛教精义为根底,对世俗社会万千的人和事,即人生观、财富观、爱情婚姻、家庭教育、人际交往、成功励志等诸方面行阐释,勘破纷扰表象,指向自省自在的人生幸福,一如清躁甘霖,世洞明,让人身心善美。

舍得:星云大师的人生经营课

¥14.00

在《舍得》中,星云大师继续释发学识精义,对大众人生拓展、学业、事业、生活及修养心性诸方面行分析和指导,启发人在成长成功的过程中把握住自己,沿着精的方向完善自我,以和谐社会。

国学大书院17:反经

¥14.00

《反经》是一本实用性韬略奇书,由唐代赵蕤所著。它以唐以前的汉族历史为论证素材,集诸子百家学说于一体,融合儒、道、兵、法、阴阳、农等诸家思想,所讲内容涉及政治、外交、军事等各种领域,并且还能自成一家,形成一部逻辑体系严密、涵盖文韬武略的谋略全书。为历代有政绩的帝王将相所共悉,被尊奉为小《资治通鉴》,是丰富、深厚的汉族传统文化中的瑰宝。

购物车

购物车 个人中心

个人中心