The Tragedy of Julius Caesar

¥18.74

Mülkiyet kar??t? ya?l? anar?ist, hayat?n?n son y?llar?nda ironik bir durumda kald?. ?svi?re vatanda?l???na girmenin yollar?n? arayan Bakunin'e sunulan se?enek, orada bir ev sahibi olmas?yd? ve belki de en hazini, sahip olaca?? bu ev nedeniyle, polisin, resm? tutanaklara “Michael Bakunin, rantiye” notunu dü?mesiydi. 18 May?s 1814'te Rusya'da do?an Michael Aleksandrovich Bakunin, 1 Temmuz 1876'da ?ldü?ünde ülkesinden ?ok uzaklardayd? ve cenazesinde yaln?zca 30–40 ki?i vard?. Gen? Bakunin i?in, “A?k, insan?n yeryüzündeki en üst misyonuydu. Bir insan?n kendini a?ks?z vermesi, Kutsal Ruh’a kar?? i?lenmi? bir günaht?”.. ?Kad?nlar taraf?ndan olduk?a ?ekici bulunan Mihail'in ise kad?nlarla ili?kisi hep ruhsal bir a?k olarak kald?.??svi?re'nin muhte?em manzaras? e?li?inde George Sand romanlar? okuyan Bakunin, Frans?z dü?üncesinin Alman dü?üncesinden üstün oldu?u inanc?n? sa?lamla?t?r?yordu. ? Bakunin, Marx i?in, “O, beni duygusal idealist olarak adland?r?yordu; hakl?yd?. Ben de onu, hoyrat, kendini be?enmi? ve ac?mas?z olarak de?erlendiriyordum; ben de hakl?yd?m” diyordu.. ? Kendisine ili?kin konularda kindar olmayan Bakunin, Herzen'in kar?s?na g?sterdi?i so?uklu?u hayat?n?n sonuna kadar unutamad?.?“Art?k reaksiyonun muzaffer gü?lerine kar?? Sisifos'un ta??n? yuvarlamak i?in ne gerekli güce ne de güvene sahibim. Bu yüzden, mücadeleden ?ekiliyor ve arkada?lar?mdan tek bir iyilik bekliyorum: "Unutulmak”,?Orta ve ge? on dokuzuncu yüzy?lda, radikal sol –yani, a?g?zlü kapitalizm ele?tirmenleri ve sanayi i??ilerinin ?zgürlü?ünün savunucular?– iki temel franksiyona ayr?l?yordu: Marksistler ve anar?istler. Kabaca s?ylemek gerekirse (ki bu son derece kar???k bir hik?yedir), kazanan Marksistler oldu ve yirminci yüzy?l?n tüm ba?ar?l? sol devrimleri –Rus, ?in ve Küba, ?rne?in– Marksist ilkelere ba?l?l?klar?n? ilan ettiler. ? Marksistler ile anar?istler aras?ndaki sava? bu noktada tarihsel bir meraktan ?te devam eden bir meseledir. Pi?man olmayan ya da ele?tirilmeyen tek ger?ek Marksist sol Kim Jong Il ve taraf etraftaki birka? entelektüel ve profes?rdür. Anar?izm ise uygulanabilir bir toplumsal hareket olarak ?kinci Dünya Sava??yla yava? yava? tükenmeye yüz tutmu?ken küreselle?me kar??t? hareket ve d?nemimizin di?er radikalizmleri i?inde yeniden dirilmeye ba?lam??t?r. ? Ne var ki, d?neminde –Marx’?n di?erleriyle aras?ndaki– bu sava? bir ?lüm kal?m meselesiydi ve Marksizm muhtemel kapitalizm kar??t? olarak ve yan? s?ra anar?izm kar??t? olarak tan?mlan?yordu. Asl?nda, Marx’?n yazarl??? anar?izme y?nelik sald?r?lar? a??s?ndan handiyse gülün? bir geni?li?e ula?m??t?r. Marx’?n Alman ?deolojisi kitab?n?n büyük b?lümü –yüzlerce sayfas?– bireyci/anar?ist Max Stirner’e y?nelik bir sald?r?dan ibarettir. Felsefenin Sefaleti Proudhon’a kar?? büyük?e bir fikir sava??d?r. Marx onca zaman ve enerjisini Bakunin’e sald?rmaya harcam??t?r: ?“dangalak!”?“canavar, et ve ya? y???n?,” “sap?k” vesaire: ?bu tabirler, has?mlar? s?z konusu oldu?unda Marx’?n bildik üslubudur: yazarl??? yar? bilimsel inceleme, yar? s?zlü tacizdir. Marx’?n, gerek kendi a?z?ndan gerekse de kimi s?zcülerini kullanarak ony?llar boyunca y?neltti?i ve muhtemelen di?erleri denli e?lenceli olmayan var olan su?lamas?, Bakunin’in bir muhbir oldu?u y?nündeydi ve Marx’?n bu ba?ar?l? sald?r?lar? nihayetinde Bakunin’in Enternasyonal ???i Z?mb?rt?s?ndan tasfiyesine yol a?t?.. ?

Unicat. Cartea cu o sut? de finaluri

¥48.97

O parte dintre noi au tr?it vremuri grele pe care uneori le mai vis?m, le povestim sau despre care scriem ?nc?, f?r? patima cumplit? care i-a cuprins pe profitorii de atunci, care ?i ast?zi ne fac r?u, ?i chiar mai r?u dec?t ?pe vremea aceea“, cum se zice. E drept c? noi am prev?zut-o ?ntr-un fel sau altul, spun?nd-o celor care se-ncumetau s? ne asculte, f?r? preten?ia, Doamne, fere?te!, de a ne considera ?i disiden?i, cum o f?cur? cei men?iona?i mai sus. Previziunile noastre s-au bazat pe o anume cunoa?tere a mersului istoriei, care, cum se ?tie, se tot repet?, cu mici deosebiri, fire?te. Oricum, ceva cuno?tin?e de economie politic? nu ne stric? nici ?n zilele noastre, pentru a ne da seama de jocul frecvent al trecerii de la economia politic? la politica economic? ?i, mai ales, al trecerilor de la un sistem sau or?nduire economic? la alta ?i invers, cum le-am tr?it noi: de la capitalism la socialism ?i viceversa. Ca un fel de ciud??enie, au r?mas considera?iunile despre noul eon sau noua er? (New Age) ale filosofului din Lancr?m, mai ales c? acestea s-au realizat abia dup? c?derea comunismului, pe care n-o mai prev?zuse Blaga. (Alexandru Surdu) Eseuri filosofice de acela?i autor 1. Voca?ii filosofice rom?ne?ti, Editura Aca?de?miei Rom?ne, Bucure?ti, 1995, 216 p.; edi??ia a II-a, Editura Ardealul, T?rgu-Mure?, 2003, 206 p. 2. Confluen?e cultural-filosofice, Editura Pai?de?ia, Bucure?ti, 2002, 219 p. 3. M?rturiile anamnezei, Editura Paideia, Bu?cu?re?ti, 2004, 193 p. 4. Comentarii la rostirea filosofic?, Editura Kron-Art, Bra?ov, 2009, 186 p. 5. Izvoare de filosofie rom?neasc?, Editura Biblioteca Bucure?tilor, Bucure?ti, 2010, 171 p.; edi?ia a II-a, Editura Renaissance, Bucu?re?ti, 2011, 161 p. 6. A sufletului rom?nesc cinstire, Editura Re?naissance, Bucure?ti, 2011, 197 p. 7. Pietre de poticnire, Editura Ardealul, T?r?gu-Mure?, 2014, 179 p.

Confesiunile unei dependente de art?

¥57.14

One of the greatest works of philosophy, political theory, and literature ever produced, Plato’s Republic has shaped Western thought for thousands of years, and remains as relevant today as when it was written during the fourth century B.C.Republic begins by posing a central question: "What is justice, and why should we be just, especially when the wicked often seem happier and more successful?" For Plato, the answer lies with the ways people, groups, and institutions organize and behave. A brilliant inquiry into the problems of constructing the perfect state, and the roles education, the arts, family, and religion should play in our lives, Republic employs picturesque settings, sharply outlined characters, and conversational dialogue to drive home the philosopher’s often provocative arguments.Highly regarded as one of the most accurate renderings of Plato's Republic that has yet been published, this widely acclaimed work is the first strictly literal translation of a timeless classic. This Special Collector's Edition includes a new introduction by Prof. Colin Kant, PH.D, a noted Platonian and Socratic scholar.

Nagyapó mesésk?nyve

¥22.73

...a knyvet ne tekintsük úgy, mint amelynek a fejldése már befejezdtt, és amin már nincs is mit tkéletesíteni... azzal mintha nem foglalkozna senki, hogy a knyvet miként lehetne az olvasó számára használhatóbbá tenni... nagyon is el tudnék képzelni ergonomikusabban megtervezett és knnyebben kézben tartható knyvet is (amelyet nem ejtek el, ha a mobilom után kezdek kotorászni a 6-os villamoson. Ha egyszer vehetünk jobban kézbe ill tollat, akkor talán ez sem képtelenség).”

Enders

¥65.32

Dialoguri cu Vasile Dem. Zamfirescu consemnate de Leonid DragomirLa Facultatea de Filosofie din Bucure?ti unde eram studen?i exista pe atunci mult? libertate ?n alegerea cursurilor pe care doream s? le urm?m. Se afi?a la ?nceputul anului universitar o list? a cursurilor obligatorii ?i op?ionale, acestea din urm? fiind majoritare. A?a am descoperit cursul de Psihanaliz? filosofic? al profesorului Vasile Dem. Zamfirescu, despre care ?tiam vag c? fusese unul dintre discipolii lui Constantin Noica. Atmosfera de libertate ?n care ne mi?cam se reg?sea ?n totalitate aici. Cursul ne interesa at?t prin con?inutul lui — care adolescent n-a fost fascinat de psihanaliz?! — c?t ?i prin rigoarea ?i claritatea expunerii. De?i nu mai predase p?n? atunci, Vasile Dem. Zamfirescu era cu adev?rat profesor. Seminariile erau ?ns? ale noastre. Aici se iscau polemici, se propuneau interpret?ri insolite, se scriau ?i se citeau eseuri inspirate de noile probleme ?i lecturi. De obicei dep??eam limitele temei propuse, astfel ?nc?t totul ar fi putut degenera ?ntr-un dialog al surzilor sau ?n divaga?ii sterile dac? n-ar fi existat polul magnetic: profesorul. Nu numai c? el aducea, cu mult tact, discu?ia pe f?ga?ul normal, la obiect, dar opiniile noastre, oric?t de ?ndr?zne?e, vizau direct sau indirect aprobarea lui. Aceasta uneori venea, alteori nu, dar ceea ce conta pentru noi era faptul de a ne ?ti asculta?i. Sim?eam c? el poate s? vad? ?n spusele noastre sau dincolo de ele personalitatea noastr? ?ntreag?. De aceea voiam s? d?m totul ?n acele seminarii care treceau at?t de repede, de?i discu?iile se prelungeau ?n pauze ?i dup? ?ncheierea lor.

Mindig is éjjel lesz

¥69.65

Sri Krsna számtalan univerzum vitathatatlan Ura, akit korlátlan er?, gazdagság, hírnév, tudás és lemondás jellemez, ám ezek az ?r?kké diadalmas energiák csupán részben tárják fel ?t. Végtelen dics?ségét csak az ismerheti meg, aki elb?v?l? szépségénél keres menedéket, ?sszes t?bbi fenséges tulajdonsága forrásánál, melynek páratlan transzcendentális teste ad otthont. Szépségének legf?bb jellemz?je az a mindenek f?l?tt álló édes íz, ami t?mény kivonata mindennek, ami édes. Minden édes dolgot túlszárnyal, és nem más, mint az édes íz megízlelésének képessége. Sri Krsna édes természete finom arany sugárzásként ragyog át transzcendentális testén. Govinda páratlanul gy?ny?r? testének legszebb és legédesebb része ragyogó arca. ?des hold-arcán rejtélyes mosolya a legédesebb, az az arcáról ragyogó ezüst holdsugár, ami nektárral árasztja el a világot. Mosolyának sugárzása nélkül keser? lenne a cukor, savanyú a méz, és a nektárnak sem lenne íze. Amikor mosolyának holdsugara elvegyül teste ragyogásával, a kett? együtt a kámfor aromájára emlékeztet. Ez a kámfor aztán ajkán keresztül a fuvolába kerül, ahonnan megfoghatatlan hangvibrációként t?r el?, és er?nek erejével rabul ejti azoknak az elméjét, akik hallják. Ahogy a szavak gondolatok mondanivalóját hordozzák, ahogy a gondolatok a szemben tükr?z?dnek, ahogy egy mosoly a szív érzelmeir?l árulkodik, úgy a fuvola hangja Sri Krsna szépségét viszi a fül?n keresztül a szív templomának oltárára.

A kalózkirály

¥8.67

Euthyphro (Ancient Greek: Euthuphron) is one of Plato's early dialogues, dated to after 399 BC. Taking place during the weeks leading up to Socrates' trial, the dialogue features Socrates and Euthyphro, a religious expert also mentioned at Cratylus 396a and 396d, attempting to define piety or holiness. Background The dialogue is set near the king-archon's court, where the two men encounter each other. They are both there for preliminary hearings before possible trials (2a).Euthyphro has come to lay manslaughter charges against his father, as his father had allowed one of his workers to die exposed to the elements without proper care and attention (3e–4d). This worker had killed a slave belonging to the family estate on the island of Naxos; while Euthyphro's father waited to hear from the expounders of religious law (exegetes cf. Laws 759d) about how to proceed, the worker died bound and gagged in a ditch. Socrates expresses his astonishment at the confidence of a man able to take his own father to court on such a serious charge, even when Athenian Law allows only relatives of the deceased to sue for murder. Euthyphro misses the astonishment, and merely confirms his overconfidence in his own judgment of religious/ethical matters. In an example of "Socratic irony," Socrates states that Euthyphro obviously has a clear understanding of what is pious and impious. Since Socrates himself is facing a charge of impiety, he expresses the hope to learn from Euthyphro, all the better to defend himself in his own trial. Euthyphro claims that what lies behind the charge brought against Socrates by Meletus and the other accusers is Socrates' claim that he is subjected to a daimon or divine sign which warns him of various courses of action (3b). Even more suspicious from the viewpoint of many Athenians, Socrates expresses skeptical views on the main stories about the Greek gods, which the two men briefly discuss before plunging into the main argument. Socrates expresses reservations about such accounts which show up the gods' cruelty and inconsistency. He mentions the castration of the early sky god, Uranus, by his son Cronus, saying he finds such stories very difficult to accept (6a–6c). Euthyphro, after claiming to be able to tell even more amazing such stories, spends little time or effort defending the conventional view of the gods. Instead, he is led straight to the real task at hand, as Socrates forces him to confront his ignorance, ever pressing him for a definition of 'piety'. Yet, with every definition Euthyphro proposes, Socrates very quickly finds a fatal flaw (6d ff.). At the end of the dialogue, Euthyphro is forced to admit that each definition has been a failure, but rather than correct it, he makes the excuse that it is time for him to go, and Socrates ends the dialogue with a classic example of Socratic irony: since Euthyphro has been unable to come up with a definition that will stand on its own two feet, Euthyphro has failed to teach Socrates anything at all about piety, and so he has received no aid for his own defense at his own trial (15c ff.).

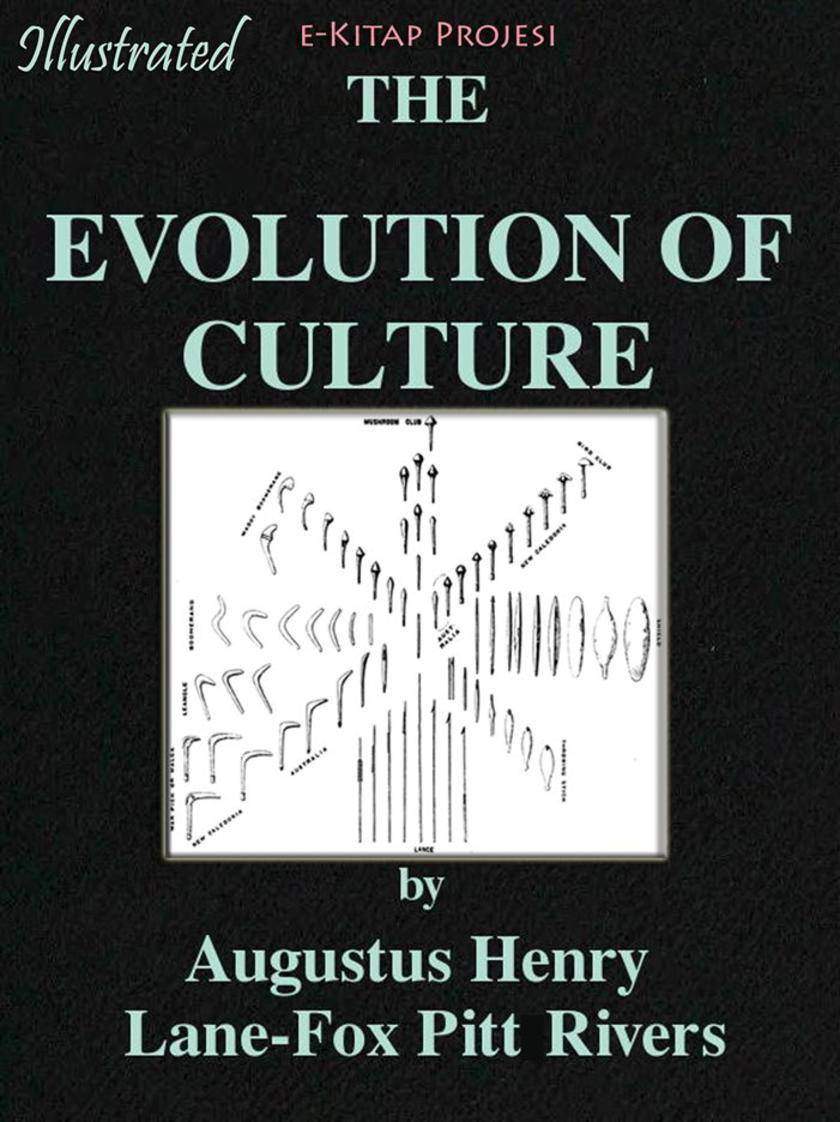

Evolution of the Culture

¥28.04

Paradise Lost is an epic poem in blank verse by the 17th-century English poet John Milton (1608–1674). The first version, published in 1667, consisted of ten books with over ten thousand lines of verse. A second edition followed in 1674, arranged into twelve books (in the manner of Virgil's Aeneid) with minor revisions throughout and a note on the versification. It is considered by critics to be Milton's "major work", and helped solidify his reputation as one of the greatest English poets of his time. The poem concerns the Biblical story of the Fall of Man: the temptation of Adam and Eve by the fallen angel Satan and their expulsion from the Garden of Eden. Milton's purpose, stated in Book I, is to "justify the ways of God to men" Short Summary:The poem is separated into twelve "books" or sections, the lengths of which vary greatly (the longest is Book IX, with 1,189 lines, and the shortest Book VII, with 640). The Arguments at the head of each book were added in subsequent imprints of the first edition. Originally published in ten books, a fully "Revised and Augmented" edition reorganized into twelve books was issued in 1674, and this is the edition generally used today. The poem follows the epic tradition of starting in medias res (Latin for in the midst of things), the background story being recounted later.Milton's story has two narrative arcs, one about Satan (Lucifer) and the other following Adam and Eve. It begins after Satan and the other rebel angels have been defeated and banished to Hell, or, as it is also called in the poem, Tartarus. In Pand?monium, Satan employs his rhetorical skill to organise his followers; he is aided by Mammon and Beelzebub. Belial and Moloch are also present. At the end of the debate, Satan volunteers to poison the newly created Earth and God's new and most favoured creation, Mankind. He braves the dangers of the Abyss alone in a manner reminiscent of Odysseus or Aeneas. After an arduous traversal of the Chaos outside Hell, he enters God's new material World, and later the Garden of Eden. At several points in the poem, an Angelic War over Heaven is recounted from different perspectives. Satan's rebellion follows the epic convention of large-scale warfare. The battles between the faithful angels and Satan's forces take place over three days. At the final battle, the Son of God single-handedly defeats the entire legion of angelic rebels and banishes them from Heaven. Following this purge, God creates the World, culminating in his creation of Adam and Eve. While God gave Adam and Eve total freedom and power to rule over all creation, He gave them one explicit command: not to eat from the Tree of the knowledge of good and evil on penalty of death.

Heart of Darkness

¥9.07

The Republic (Greek: Politeia) is a Socratic dialogue, written by Plato around 380 BC, concerning the definition of (justice), the order and character of the just city-state and the just man, reason by which ancient readers used the name On Justice as an alternative title (not to be confused with the spurious dialogue also titled On Justice). The dramatic date of the dialogue has been much debated and though it must take place some time during the Peloponnesian War, "there would be jarring anachronisms if any of the candidate specific dates between 432 and 404 were assigned". It is Plato's best-known work and has proven to be one of the most intellectually and historically influential works of philosophy and political theory. In it, Socrates along with various Athenians and foreigners discuss the meaning of justice and examine whether or not the just man is happier than the unjust man by considering a series of different cities coming into existence "in speech", culminating in a city (Kallipolis) ruled by philosopher-kings; and by examining the nature of existing regimes. The participants also discuss the theory of forms, the immortality of the soul, and the roles of the philosopher and of poetry in society. Short Summary (Epilogue):X.1—X.8. 595a—608b. Rejection of Mimetic ArtX.9—X.11. 608c—612a. Immortality of the SoulX.12. 612a—613e. Rewards of Justice in LifeX.13—X.16. 613e—621d. Judgment of the Dead The paradigm of the city — the idea of the Good, the Agathon — has manifold historical embodiments, undertaken by those who have seen the Agathon, and are ordered via the vision. The centre piece of the Republic, Part II, nos. 2–3, discusses the rule of the philosopher, and the vision of the Agathon with the allegory of the cave, which is clarified in the theory of forms. The centre piece is preceded and followed by the discussion of the means that will secure a well-ordered polis (City). Part II, no. 1, concerns marriage, the community of people and goods for the Guardians, and the restraints on warfare among the Hellenes. It describes a partially communistic polis. Part II, no. 4, deals with the philosophical education of the rulers who will preserve the order and character of the city-state.In Part II, the Embodiment of the Idea, is preceded by the establishment of the economic and social orders of a polis (Part I), followed by an analysis (Part III) of the decline the order must traverse. The three parts compose the main body of the dialogues, with their discussions of the “paradigm”, its embodiment, its genesis, and its decline.The Introduction and the Conclusion are the frame for the body of the Republic. The discussion of right order is occasioned by the questions: “Is Justice better than Injustice?” and “Will an Unjust man fare better than a Just man?” The introductory question is balanced by the concluding answer: “Justice is preferable to Injustice”. In turn, the foregoing are framed with the Prologue (Book I) and the Epilogue (Book X). The prologue is a short dialogue about the common public doxai (opinions) about “Justice”. Based upon faith, and not reason, the Epilogue describes the new arts and the immortality of the soul. ? About Author: Plato (Greek: Platon, " 428/427 or 424/423 BC – 348/347 BC) was a philosopher in Classical Greece. He was also a mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Along with his mentor, Socrates, and his most-famous student, Aristotle, Plato helped to lay the foundations of Western philosophy and science. Alfred North Whitehead once noted: "the safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato." Plato's sophistication as a writer is evident in his Socratic dialogues; thirty-six dialogues and thirteen letters have been ascribed to him, although 15–18 of them have been contested. Plato's writings have been published in several fashions; this has led to several conventions regarding the naming and referencing of Plato's texts. Plato's dialogues have been used to teach a range of subjects, including philosophy, logic, ethics, rhetoric, religion and mathematics. Plato is one of the most important founding figures in Western philosophy. His writings related to the Theory of Forms, or Platonic ideals, are basis for Platonism. ? Early lifeThe exact time and place of Plato's birth are not known, but it is certain that he belonged to an aristocratic and influential family. Based on ancient sources, most modern scholars believe that he was born in Athens or Aegina between 429 and 423 BC. His father was Ariston. According to a disputed tradition, reported by Diogenes Laertius, Ariston traced his descent from the king of Athens, Codrus, and the king of Messenia, Melanthus. Plato's mother was Perictione, whose family boasted of a relationship with the famous Athenian lawmaker an

Скоропадський. Спогади 1917-1918

¥22.74

Potere, cortigianeria, dispotismo, libertà, uguaglianza... attuali o inattuali la satira d'Holbach e La Boétie? Cambiano i tempi e i nomi, ma la natura umana nel suo fondo negli ultimi secoli non è mutata. Com'è virtù di tutti i classici, le loro voci continuano a farci sorridere, indignare e riflettere non solo sul passato ma ugualmente sul presente e sul futuro, su quanto in esso ci possa essere di desiderabile o indesiderabile. In Appendice, i testi si possono leggere anche nella loro originaria edizione in francese. SOMMARIO?- Fabrizio Pinna, Una introduzione (in due tempi) e qualche digressione: I. Barone d'Holbach, "Quest'arte sublime dello strisciare"...; II. ?tienne de La Boétie, "Siate determinati di non voler più servire ed eccovi liberi"... . LIBERT? & POTERE: Paul Henri Thiry d'Holbach, Saggio sull'arte di strisciare ad uso dei cortigiani; Paul Henri Thiry d'Holbach, I Cortigiani; Jean le Rond d'Alembert, Cortigiano; ?tienne de La Boétie, La servitù volontaria. APPENDICE I: Libertà Uguaglianza (1799)- Il Cittadino Editore. APPENDICE II: Essai sur l’art de ramper, à l’usage des courtisans (1764) - Paul Henri Thiry d'Holbach; Des Courtisans (1773) - Paul Henri Thiry d'Holbach; Courtisan (1752) / Courtisane (1754) - Jean le Rond d'Alembert; Discours de la servitude volontaire o Contr'un (1549) - ?tienne de La Boétie.?LE COLLANE IN/DEFINIZIONI & CON(TRO)TESTI

孟子诵读本(插图版) 中华书局出品

¥22.80

《孟子诵读本》(插图版)是“中华经典诵读工程配套读本”之一,专为4—12岁的青少年儿童编写,我们依据版本收录《孟子》全文,并附有拼音,对难字、难词、难句做了精炼、准确、易懂的注释,同时,配有大量与文字密切关联的图片,让读者在愉悦的审美中,品味经典的魅力。

A leskel?d?

¥66.79

Within our Society (the International Society for Krishna Consciousness), guru has been taken to be synonymous with diksa-guru, but what about those great souls who have introduced us to Krsna consciousness? What relationship do we have with these Vaisnavas, and what are our obligations toward them, as well as toward parents, teachers, sannyasis, and other superiors who help guide us back to Godhead? Not much has been said by the Society on these topics, and hardly any appreciation is shown for those souls who labor to elevate us day by day.The scriptures, however, glorify as guru all Vaisnavas who guide a conditioned soul back to Godhead — be they instructors or initiators — advocating a culture of honor and respect. ISKCON needs to reflect upon these principles further, and the purpose of this book is to act as a catalyst toward such an end.

菜根谭(全新精编精校修订)(国学大书院)

¥11.40

《菜根谭》文字简练,对仗工整,博大精深,耐人寻味,通俗易懂,雅俗共赏;寥寥几句道出人生玄机,只言片语指明生存之道。它告诫读书人“道乃公正无私,学当随事警惕”;它提醒为官者“为官公廉。居家恕俭”。人生在世,“心善而子孙盛,根固而枝叶荣”,“清浊并包,善恶兼容”,“超然天地之外,不名利之中”,因为“人生一傀儡”,只有如此,才能“自控便超然”。

传习录(全新精编精校修订)(国学大书院)(明代思想泰斗王阳明 知行合一的行动指南)

¥7.98

立学、立言之著 ?立德、立身之典《传习录》是王阳明的问答语录和论学书信集,是一部儒家简明而有代表性的哲学著作。包含了王阳明的主要哲学思想,是研究王阳明思想及心学发展的重要资料。《传习录》不但全面阐述了王阳明的思想,同时还体现了他辩证的授课方法,以及生动活泼、善于用譬、常带机锋的语言艺术。因此该书一经问世,便受到了士人的推崇。

周易(国学大书院)(儒道之源:十三经之首 探讨“变化”的书 《易》之道,即君子之道,每天都用)

¥13.05

智慧中的智慧 ?预测学中的行为学《周易》是群经之首,是经典中之经典,哲学中之哲学,谋略中之谋略。从《周易》中,哲学家看到辩证思维,史学家看到历史兴衰,政治家看到治世方略,军事家可参悟兵法,企业家亦可从中找到经营的方法,同样,芸芸众生也可将其视为为人处世、提高修养的不二法宝。 本书将《周易》的六十四卦分别予以详细解读,每卦独立自成一体,各节皆有原文、译文、启示,每卦之后附有中外著名事例,以期抛砖引玉之效。 《周易》一书作为中国早熟的思想文化体系,它在中国传统思想文化中的重要地位,已为世所公认。《周易》被称为六经之首,就是一种证明。

霍布斯的修辞(“经典与解释”第26期)

¥28.00

重拾中西方古典学问坠绪,不仅因为现代性问题迫使学问古共智慧,更因为古学问关乎亘古不移的人世问题。古学经典需要解释,解释是涵养精神的活动,也是思想取向的抉择;宁可跟随柏拉图犯错,也不与那伙人一起正确。举凡疏证诠解中国古学经典、移译西学整理旧故的晚近成果,不外乎愿与中西方古典大智慧一起思想,以期寻回精神的涵养,不负教书育人的人类亘古基业。 本书是《经典与解释》系列之一的《霍布斯的修辞》分册,内中具体研究了“霍布斯的哲学思想”,主要收录了:霍布斯《利维坦》中的推理与修辞、霍布斯的“非亚里士多德”政治修辞学、“教条”对抗“数理”、基督教国家的自然法等内容。

人论

¥39.80

《人论》是文化哲学创始人卡西尔生前出版的*后一部著作,是其毕生理论的浓缩,在其著作中是*为著名、流传*广、影响力*的一本。全书围绕"人是什么"这一问题,旁征博引,高屋建瓴,独树一帜地提出了"人是符号动物"这一观,指出"人不仅生活在自然物质宇宙中,还生活在符号宇宙中"的事实。 全书分上下两篇,上篇"人是什么"着力探讨了人与动物的分野以及人的符号创造性特;下篇"人与文化"则对人类文化各个形态与现象,如神话、宗教、语言、艺术、历史、科学等,行深浅出的分析探索,自"符号"出发解读人类与人类文化的关系。 人类对于自我认识的探索永不停息,而卡西尔则给予了我们一个睿智精妙的解答。

人生的智慧

¥14.82

《人生的智慧》取自德国思想家叔本华的《附录和补遗》,而实际上是独立成书的,阐述了生活的本质及如何在生活中获得幸福,所讨论的事情与我们的世俗生活极为近,如健康、财富、荣誉、名声、待人物所应遵循的原则等。正如叔本华所说的,在《人生智慧丛书:人生的智慧(插图版)》里,他尽量从世俗、实用的角度考虑问题。因此,《人生智慧丛书:人生的智慧(插图版)》尤其适合大众阅读。 书中含有几分孤芳自赏的自我辩白和自我激励,甚至还流露着顾影自怜的几丝悲凉、几许惆怅,但更多的还是他因为自尊而隐匿在文中的深刻的自我剖析和感悟,以及由此而来的坚定与自信、清醒与睿智。 《人生智慧丛书:人生的智慧(插图版)》插了七十余幅摄影作品,由自由摄影师闰笑枫摄影并首次出版,与主题非常呼应。

20世纪分析哲学史卷二

¥56.24

分析哲学是20世纪主要的两大哲学流派之一,自摩尔、罗素以来,大师辈出,经典产品层出不穷,可以说,整个改变了西方哲学的面貌。本书是探讨20世纪分析哲学的一部巨著,作者是著名的分析哲学家,在书中详尽地考察了从摩尔、罗素、维特根斯坦到蒯因、克里普克等大师的哲学思想,对其在哲学史上的主要贡献做了极其精彩的分析,对其论证中的不足同样做了犀利的批评。可以说,本书必将作为一部经典的哲学史而流传后世。第二卷通过如下哲学家或学派来解释分析传统在接下来的四分之一个世纪里的演变:首先是后期维特根斯坦和英国的日常语言学派,然后是威拉德·冯·奥曼·蒯因在科学启发下向自然主义的转变,以及这种转变与唐纳德·戴维森的语言理论的融合,后是索尔·克里普克对必然性和先天性的概念重构,这种重构改变了分析哲学的轨迹。正是这个时候,分析的传统背离了关于哲学的语言观念,并回归到把逻辑和语言作为哲学理论化的有力工具的早期视野中去。尽管关于哲学的语言视野失败了,但我们在理解哲学各个领域的核心问题方面还是取得了很大进展。第二卷讲述了上述故事,而它的“尾声”部分勾勒了二十世纪结束之际哲学专业化的多元化新纪元。

查拉图斯特拉如是说

¥98.00

当善与恶的界限日益模糊, 当一切坚固的东西都烟消云散, 当生命之轻已变得不能承受, 我们该从哪里求得生存的意义? 是重造崇拜偶像?还是干脆沦于虚无,一路娱乐至死? 在人类刚刚步现代世界时,德国哲人尼采就严肃地思考上述问题--而一切答案,都汇聚到《查拉图斯特拉如是说》这部哲学小说中。通过主人公查拉图斯特拉的漫游与教诲,尼采发出了先知般的宣言:在"上帝已死"的时代,人应该直面虚无,从自身创造生命的意义,*终化为能撑起生命重担的超人!

叶秀山全集·第二卷

¥65.00

【内容简介】 本选题分类结集叶秀山先生全部已经出版的专著,在学术期刊上发表的所有论文,以及部分笔记、札记、书信和讲演录,共11卷。本选题代表了当代中国哲学的高度,是哲学专业学 习者和研究者的重要学习和参考用书。第二卷包括《书法美学引论》《古中国的歌》《思·史·诗》三本专著。

购物车

购物车 个人中心

个人中心