Bolondok hercege

¥73.49

“Goodbye, said the fox. And now here is my secret, a very simple secret. It is only with the heart that one can see rightly. What is essential is invisible to the eye.” Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince The Little Prince first published in 1943, is a novella and the most famous work of the French aristocrat, writer, poet and pioneering aviator Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. The novella is both the most read and most translated book in the French language, and was voted the best book of the 20th century in France. Translated into more than 250 languages and dialects selling over a million copies per year with sales totalling more than 140 million copies worldwide, it has become one of the best-selling books ever published. Saint-Exupéry, a laureate of several of France's highest literary awards and a reserve military pilot at the start of the Second World War, wrote and illustrated the manuscript while exiled in the United States after the Fall of France. He had travelled there on a personal mission to persuade its government to quickly enter the war against Nazi Germany. In the midst of personal upheavals and failing health he produced almost half of the writings he would be remembered for, including a tender tale of loneliness, friendship, love and loss, in the form of a young prince fallen to Earth.

The Mysterious Island

¥8.67

Hard Times – For These Times (commonly known as "Hard Times") is the tenth novel by Charles Dickens, first published in 1854. The book appraises English society and highlights the social and economic pressures of the times. Hard Times is unusual in several respects. It is by far the shortest of Dickens' novels, barely a quarter of the length of those written immediately before and after it. Also, unlike all but one of his other novels, Hard Times has neither a preface nor illustrations. Moreover, it is his only novel not to have scenes set in London. Instead the story is set in the fictitious Victorian industrial Coketown, a generic Northern English mill-town, in some ways similar to Manchester, though smaller. Coketown may be partially based on 19th-century Preston. One of Dickens's reasons for writing Hard Times was that sales of his weekly periodical, Household Words, were low, and it was hoped the novel's publication in instalments would boost circulation – as indeed proved to be the case. Since publication it has received a mixed response from critics. Critics such as George Bernard Shaw and Thomas Macaulay have mainly focused on Dickens's treatment of trade unions and his post–Industrial Revolution pessimism regarding the divide between capitalist mill owners and undervalued workers during the Victorian era. F. R. Leavis, a great admirer of the book, included it—but not Dickens' work as a whole—as part of his Great Tradition of English novels. ***‘Now, what I want is, Facts. Teach these boys and girls nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing else, and root out everything else. You can only form the minds of reasoning animals upon Facts: nothing else will ever be of any service to them. This is the principle on which I bring up my own children, and this is the principle on which I bring up these children. Stick to Facts, sir!’ ? ?The scene was a plain, bare, monotonous vault of a school-room, and the speaker’s square forefinger emphasized his observations by underscoring every sentence with a line on the schoolmaster’s sleeve. The emphasis was helped by the speaker’s square wall of a forehead, which had his eyebrows for its base, while his eyes found commodious cellarage in two dark caves, overshadowed by the wall. The emphasis was helped by the speaker’s mouth, which was wide, thin, and hard set. The emphasis was helped by the speaker’s voice, which was inflexible, dry, and dictatorial. The emphasis was helped by the speaker’s hair, which bristled on the skirts of his bald head, a plantation of firs to keep the wind from its shining surface, all covered with knobs, like the crust of a plum pie, as if the head had scarcely warehouse-room for the hard facts stored inside. The speaker’s obstinate carriage, square coat, square legs, square shoulders,—nay, his very neckcloth, trained to take him by the throat with an unaccommodating grasp, like a stubborn fact, as it was,—all helped the emphasis. ‘In this life, we want nothing but Facts, sir; nothing but Facts!’The speaker, and the schoolmaster, and the third grown person present, all backed a little, and swept with their eyes the inclined plane of little vessels then and there arranged in order, ready to have imperial gallons of facts poured into them until they were full to the brim.

Akik kétszer halnak meg

¥8.67

Emile, or On Education or ?mile, Or Treatise on Education (French: ?mile, ou De l’éducation) is a treatise on the nature of education and on the nature of man written by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who considered it to be the “best and most important of all my writings”. Due to a section of the book entitled “Profession of Faith of the Savoyard Vicar,” Emile was banned in Paris and Geneva and was publicly burned in 1762, the year of its first publication. During the French Revolution, Emile served as the inspiration for what became a new national system of education. The work tackles fundamental political and philosophical questions about the relationship between the individual and society— how, in particular, the individual might retain what Rousseau saw as innate human goodness while remaining part of a corrupting collectivity. Its opening sentence: “Everything is good as it leaves the hands of the Author of things; everything degenerates in the hands of man.” Rousseau seeks to describe a system of education that would enable the natural man he identifies in The Social Contract (1762) to survive corrupt society. He employs the novelistic device of Emile and his tutor to illustrate how such an ideal citizen might be educated. Emile is scarcely a detailed parenting guide but it does contain some specific advice on raising children. It is regarded by some as the first philosophy of education in Western culture to have a serious claim to completeness, as well as being one of the first Bildungsroman novels, having preceded Goethe's Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship by more than thirty years. ? About Author: Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712 – 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer of the 18th century. His political philosophy influenced the French Revolution as well as the overall development of modern political, sociological, and educational thought. Rousseau's novel ?mile, or On Education is a treatise on the education of the whole person for citizenship. His sentimental novel Julie, or the New Heloise was of importance to the development of pre-romanticism and romanticism in fiction. Rousseau's autobiographical writings — his Confessions, which initiated the modern autobiography, and his Reveries of a Solitary Walker — exemplified the late 18th-century movement known as the Age of Sensibility, and featured an increased focus on subjectivity and introspection that later characterized modern writing. His Discourse on the Origin of Inequality and his On the Social Contract are cornerstones in modern political and social thought. He argued that private property was conventional and the beginning of true civil society. Rousseau was a successful composer of music, who wrote seven operas as well as music in other forms, and made contributions to music as a theorist. As a composer, his music was a blend of the late Baroque style and the emergent Classical fashion, and he belongs to the same generation of transitional composers as Christoph Willibald Gluck and C.P.E. Bach. One of his more well-known works is the one-act opera Le devin du village, containing the duet "Non, Colette n'est point trompeuse" which was later rearranged as a standalone song by Beethoven. During the period of the French Revolution, Rousseau was the most popular of the philosophes among members of the Jacobin Club. Rousseau was interred as a national hero in the Panthéon in Paris, in 1794, 16 years after his death..

14

¥51.58

BOW-WOW AND MEW-MEW is one of the few books for beginners in reading that may be classed as literature. Written in words of mostly one syllable, it has a story to tell, which is related in so attractive a manner as to immediately win the favor of young children. It teaches English and English literature to the child in the natural way: through a love for the reading matter. It is the character of story that will, in the not distant future, replace the ordinary primer or reader with detached sentences, and which seldom possesses any relation to literature.The ultimate objects of any story can only be effected through the love for a story. The prominent point in this story is development of good character, which may well be regarded as the highest purpose of education. The transformation from bad to good traits in the dog and cat cannot but have a desirable effect on every child that reads the story. Bow-Wow and Mew-Mew become dissatisfied with their home and their surroundings, and ungrateful toward their benefactress. As the story tells, "They did not find good in any thing." But after running away and suffering hunger, neglect, and bad treatment, their characters begin to change. They naturally come to reflect their mistress's goodness. They learn the value of companionship and friendship, and the appreciation of a home. However, the ethical thoughts in the story are presented without a moral. The child really lives the scenes described. He has the emotions of the characters and feels their convictions. And this determines the worth of a story as an agent in character development.The narrative furnishes, further, the proper kind of exercise for the imagination. It affords abundant opportunity for the play of the dramatic instinct in the child, and effects a happy union of the "home world" and the "school world." The illustrations, drawn by Miss Hodge, have been planned and executed with considerable care.

Botticelli: "Masterpieces In Colour" Series BOOK-II

¥32.62

As in the case of "The Bases of Design," to which this is intended to form a companion volume, the substance of the following chapters on Line and Form originally formed a series of lectures delivered to the students of the Manchester Municipal School of Art. There is no pretension to an exhaustive treatment of a subject it would be difficult enough to exhaust, and it is dealt with in a way intended to bear rather upon the practical work of an art school, and to be suggestive and helpful to those face to face with the current problems of drawing and design. These have been approached from a personal point of view, as the results of conclusions arrived at in the course of a busy working life which has left but few intervals for the elaboration of theories apart from practice, and such as they are, these papers are now offered to the wider circle of students and workers in the arts of design as from one of themselves. They were illustrated largely by means of rough sketching in line before my student audience, as well as by photographs and drawings. The rough diagrams have been re-drawn, and the other illustrations reproduced, so that both line and tone blocks are used, uniformity being sacrificed to fidelity.? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?WALTER CRANE. Outline, one might say, is the Alpha and Omega of Art. It is the earliest mode of expression among primitive peoples, as it is with the individual child, and it has been cultivated for its power of characterization and expression, and as an ultimate test of draughtsmanship, by the most accomplished artists of all time. The old fanciful story of its origin in the work of a lover who traced in charcoal the boundary of the shadow of the head of his sweetheart as cast upon the wall by the sun, and thus obtained the first profile portrait, is probably more true in substance than in fact, but it certainly illustrates the function of outline as the definition of the boundaries of form.Silhouette As children we probably perceive forms in nature defined as flat shapes of colour relieved upon other colours, or flat fields of light on dark, as a white horse is defined upon the green grass of a field, or a black figure upon a background of snow.Definition of BoundariesTo define the boundaries of such forms becomes the main object in early attempts at artistic expression. The attention is caught by the edges—the shape of the silhouette which remains the paramount means of distinction of form when details and secondary characteristics are lost; as the outlines of mountains remain, or are even more clearly seen, when distance subdues the details of their structure, and evening mists throw them into flat planes one behind the other, and leave nothing but the delicate lines of their edges to tell their character. We feel the beauty and simplicity of such effects in nature. We feel that the mind, through the eye resting upon these quiet planes and delicate lines, receives a sense of repose and poetic suggestion which is lost in the bright noontide, with all its wealth of glittering detail, sharp cut in light and shade. There is no doubt that this typical power of outline and the value of simplicity of mass were perceived by the ancients, notably the Ancient Egyptians and the Greeks, who both, in their own ways, in their art show a wonderful power of characterization by means of line and mass, and a delicate sense of the ornamental value and quality of line. Formation of LettersRegarding line—the use of outline from the point of view of its value as a means of definition of form and fact—its power is really only limited by the power of draughtsmanship at the command of the artist. From the archaic potters' primitive figures or the rudimentary attempts of children at human or animal forms up to the most refined outlines of a Greek vase-painter, or say the artist of the Dream of Poliphilus, the difference is one of degree.

A marsi

¥73.49

The book tells the adventures of five American prisoners of war on an uncharted island in the South Pacific. Begining in the American Civil War, as famine and death ravage the city of Richmond, Virginia, five northern POWs decide to escape in a rather unusual way – by hijacking a balloon! This is only the beginning of their adventures...

All In The Mind: Illustrated

¥4.58

The Jungle Book (1894) is a collection of stories by English Nobel laureate Rudyard Kipling. The stories were first published in magazines in 1893–94. The original publications contain illustrations, some by Rudyard's father, John Lockwood Kipling. Kipling was born in India and spent the first six years of his childhood there. After about ten years in England, he went back to India and worked there for about six-and-a-half years. These stories were written when Kipling lived in Vermont. There is evidence that it was written for his daughter Josephine, who died in 1899 aged six, after a rare first edition of the book with a poignant handwritten note by the author to his young daughter was discovered at the National Trust's Wimpole Hall in Cambridgeshire in 2010. The tales in the book (and also those in The Second Jungle Book which followed in 1895, and which includes five further stories about Mowgli) are fables, using animals in an anthropomorphic manner to give moral lessons. The verses of The Law of the Jungle, for example, lay down rules for the safety of individuals, families and communities. Kipling put in them nearly everything he knew or "heard or dreamed about the Indian jungle." Other readers have interpreted the work as allegories of the politics and society of the time. The best-known of them are the three stories revolving around the adventures of an abandoned "man cub" Mowgli who is raised by wolves in the Indian jungle. The most famous of the other stories are probably "Rikki-Tikki-Tavi", the story of a heroic mongoose, and "Toomai of the Elephants", the tale of a young elephant-handler. As with much of Kipling's work, each of the stories is preceded by a piece of verse, and succeeded by another. Characters:Akela – An Indian WolfBagheera – A melanistic (black) pantherBaloo— A Sloth BearBandar-log – A tribe of monkeysChil – A kite (renamed "Rann" in US editions)Chuchundra – A MuskratDarzee – A tailorbirdFather Wolf – The Father Wolf who raised Mowgli as his own cubGrey brother – One of Mother and Father Wolf's cubsHathi – An Indian ElephantIkki – An Asiatic Brush-tailed Porcupine (mentioned only)Kaa – Indian PythonKarait – Common KraitKotick – A White SealMang – A BatMor – An Indian PeafowlMowgli – Main character, the young jungle boyNag – A male Black cobraNagaina – A female King cobra, Nag's mateRaksha – The Mother wolf who raised Mowgli as own cubRikki-Tikki-Tavi – An Indian MongooseSea Catch – A Northern fur seal and Kotick's fatherSea Cow – A Steller's Sea CowSea Vitch – A WalrusShere Khan— A Royal Bengal TigerTabaqui – An Indian Jackal

Emma

¥23.30

A few years ago, while visiting or, rather, rummaging about Notre-Dame, the author of this book found, in an obscure nook of one of the towers, the following word, engraved by hand upon the wall:— ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ANArKH. These Greek capitals, black with age, and quite deeply graven in the stone, with I know not what signs peculiar to Gothic caligraphy imprinted upon their forms and upon their attitudes, as though with the purpose of revealing that it had been a hand of the Middle Ages which had inscribed them there, and especially the fatal and melancholy meaning contained in them, struck the author deeply. He questioned himself; he sought to divine who could have been that soul in torment which had not been willing to quit this world without leaving this stigma of crime or unhappiness upon the brow of the ancient church. Afterwards, the wall was whitewashed or scraped down, I know not which, and the inscription disappeared. For it is thus that people have been in the habit of proceeding with the marvellous churches of the Middle Ages for the last two hundred years. Mutilations come to them from every quarter, from within as well as from without. The priest whitewashes them, the archdeacon scrapes them down; then the populace arrives and demolishes them. Thus, with the exception of the fragile memory which the author of this book here consecrates to it, there remains to-day nothing whatever of the mysterious word engraved within the gloomy tower of Notre-Dame,—nothing of the destiny which it so sadly summed up. The man who wrote that word upon the wall disappeared from the midst of the generations of man many centuries ago; the word, in its turn, has been effaced from the wall of the church; the church will, perhaps, itself soon disappear from the face of the earth. It is upon this word that this book is founded.

Divine Comedy (Volume I): Paradise {Illustrated}

¥18.74

The Metamorphosis (German: Die Verwandlung, also sometimes translated as The Transformation) is a novella by Franz Kafka, first published in 1915. It has been cited as one of the seminal works of fiction of the 20th century and is studied in colleges and universities across the Western world. The story begins with a traveling salesman, Gregor Samsa, waking to find himself transformed (metamorphosed) into a large, monstrous insect-like creature. The cause of Samsa's transformation is never revealed, and Kafka never did give an explanation. The rest of Kafka's novella deals with Gregor's attempts to adjust to his new condition as he deals with being burdensome to his parents and sister, who are repulsed by the horrible, verminous creature Gregor has become. Part I: One day, Gregor Samsa, a traveling salesman, wakes up to find himself transformed into a "ungeheures Ungeziefer", literally "monstrous vermin", often interpreted as a giant bug or insect. He believes it is a dream, and reflects on how dreary life as a traveling salesman is. As he looks at the wall clock, he realizes he has overslept, and missed his train for work. He ponders on the consequences of this delay. Gregor becomes annoyed at how his boss never accepts excuses or explanations from any of his employees no matter how hard working they are, displaying an apparent lack of trusting abilities. Gregor's mother knocks on the door and he answers her. She is concerned for Gregor because he is late for work, which is unorthodox for Gregor. Gregor answers his mother and realizes that his voice has changed, but his answer is short so his mother does not notice the voice change. His sister, Grete, to whom he was very close, then whispers through the door and begs him to open the door. All his family members think that he is ill and ask him to open the door. He tries to get out of bed, but he is incapable of moving his body. While trying to move, he finds that his office manager, the chief clerk, has shown up to check on him. He finally rocks his body to the floor and calls out that he will open the door shortly.

Kurtizánok tünd?klése és nyomorúsága

¥8.67

Some people complain that science is dry. That is, of course, a matter of taste. For my own part, I like my science and my champagne as dry as I can get them. But the public thinks otherwise. So I have ventured to sweeten accompanying samples as far as possible to suit the demand, and trust they will meet with the approbation of consumers. Of the specimens here selected for exhibition, my title piece originally appeared in the Fortnightly Review: 'Honey Dew' and 'The First Potter' were contributions to Longman's Magazine: and all the rest found friendly shelter between the familiar yellow covers of the good old Cornhill. My thanks are due to the proprietors and editors of those various periodicals for kind permission to reproduce them here. G.ALLEN THE NOOK, DORKING: September, 1889. Falling In Love "..An ancient and famous human institution is in pressing danger. Sir George Campbell has set his face against the time-honoured practice of Falling in Love. Parents innumerable, it is true, have set their faces against it already from immemorial antiquity; but then they only attacked the particular instance, without venturing to impugn the institution itself on general principles. An old Indian administrator, however, goes to work in all things on a different pattern. He would always like to regulate human life generally as a department of the India Office; and so Sir George Campbell would fain have husbands and wives selected for one another (perhaps on Dr. Johnson's principle, by the Lord Chancellor) with a view to the future development of the race, in the process which he not very felicitously or elegantly describes as 'man-breeding.' 'Probably,' he says, as reported in Nature, 'we have enough physiological knowledge to effect a vast improvement in the pairing of individuals of the same or allied races if we could only apply that knowledge to make fitting marriages, instead of giving way to foolish ideas about love and the tastes of young people, whom we can hardly trust to choose their own bonnets, much less to choose in a graver matter in which they are most likely to be influenced by frivolous prejudices.' He wants us, in other words, to discard the deep-seated inner physiological promptings of inherited instinct, and to substitute for them some calm and dispassionate but artificial selection of a fitting partner as the father or mother of future generations.."

Annuska

¥8.67

The history of our English translations of "Don Quixote" is instructive. Shelton's, the first in any language, was made, apparently, about 1608, but not published till 1612. This of course was only the First Part. It has been asserted that the Second, published in 1620, is not the work of Shelton, but there is nothing to support the assertion save the fact that it has less spirit, less of what we generally understand by "go," about it than the first, which would be only natural if the first were the work of a young man writing currente calamo, and the second that of a middle-aged man writing for a bookseller. On the other hand, it is closer and more literal, the style is the same, the very same translations, or mistranslations, occur in it, and it is extremely unlikely that a new translator would, by suppressing his name, have allowed Shelton to carry off the credit. In 1687 John Phillips, Milton's nephew, produced a "Don Quixote" "made English," he says, "according to the humour of our modern language." His "Quixote" is not so much a translation as a travesty, and a travesty that for coarseness, vulgarity, and buffoonery is almost unexampled even in the literature of that day. But it is, after all, the humour of "Don Quixote" that distinguishes it from all other books of the romance kind. It is this that makes it, as one of the most judicial-minded of modern critics calls it, "the best novel in the world beyond all comparison." It is its varied humour, ranging from broad farce to comedy as subtle as Shakespeare's or Moliere's that has naturalised it in every country where there are readers, and made it a classic in every language that has a literature.

A kapitány

¥8.67

CURIOUS creatures of Animal Life have been objects of interest to mankind in all ages and countries; the universality of which may be traced to that feeling which "makes the whole world kin." The Egyptian records bear testimony to a familiarity not only with the forms of a multitude of wild animals, but with their habits and geographical distribution." The collections of living animals, now popularly known as Zoological Gardens, are of considerable antiquity. We read of such gardens in China as far back as 2,000 years; but they consisted chiefly of some favourite animals, such as stags, fish, and tortoises. The Greeks, under Pericles, introduced peacocks in large numbers from India. The Romans had their elephants; and the first giraffe in Rome, under C?sar, was as great an event in the history of zoological gardens at its time as the arrival in 1849 of the Hippopotamus was in London. The first zoological garden of which we have any detailed account is that in the reign of the Chinese Emperor, Wen Wang, founded by him about 1150 A.D., and named by him "The Park of Intelligence;" it contained mammalia, birds, fish, and amphibia. The zoological gardens of former times served their masters occasionally as hunting-grounds. This was constantly the case in Persia; and in Germany, so late as 1576, the Emperor Maximilian II. kept such a park for different animals near his castle, Neugebah, in which he frequently chased.Alexander the Great possessed his zoological gardens. We find from Pliny that Alexander had given orders to the keepers to send all the rare and curious animals which died in the gardens to Aristotle. Splendid must have been the zoological gardens which the Spaniards found connected with the Palace of Montezuma. The letters of Ferdinand Cortez and other writings of the time, as well as more recently "The History of the Indians," by Antonio Herrera, give most interesting and detailed accounts of the menagerie in Montezuma's park. The collections of animals exhibited at fairs have added little to Zoological information; but we may mention that Wombwell, one of the most noted of the showfolk, bought a pair of the first Boa Constrictors imported into England: for these he paid 75l., and in three weeks realised considerably more than that sum by their exhibition. At the time of his death, in 1850, Wombwell was possessed of three huge menageries, the cost of maintaining which averaged at least 35l. per day; and he used to estimate that, from mortality and disease, he had lost, from first to last, from 12,000l. to 15,000l. Our object in the following succession of sketches of the habits and eccentricities of the more striking animals, and their principal claims upon our attention, is to present, in narrative, their leading characteristics, and thus to secure a willing audience from old and young.

Csak a holttesteden át

¥57.47

In issuing this second treatise on Crayon Portraiture, Liquid Water Colors and French Crystals, for the use of photographers and amateur artists, I do so with the hope and assurance that all the requirements in the way of instruction for making crayon portraits on photographic enlargements and for finishing photographs in color will be fully met. To these I have added complete instructions for free-hand crayons. This book embodies the results of a studio experience of twenty-four years spent in practical work, in teaching, and in overcoming the everyday difficulties encountered, not alone in my own work, but in that of my pupils as well. Hence the book has been prepared with special reference to the needs of the student. It presents a brief course of precepts, and requires on the part of the pupil only perseverance in order that he may achieve excellence. The mechanical principles are few, and have been laid down in a few words; and, as nearly all students have felt, in the earlier period of their art work, the necessity of some general rules to guide them in the composition and arrangement of color, I have given, without entering into any profound discussion of the subject, a few of its practical precepts, which, it is hoped, will prove helpful. While this book does not treat of art in a very broad way, yet I am convinced that those who follow its teachings will, through the work they accomplish, be soon led to a higher appreciation of art. Although this kind of work does not create, yet who will say that it will not have accomplished much if it shall prove to be the first step that shall lead some student to devote his or her life to the sacred calling of art? It has been said that artists rarely, if ever, write on art, because they have the impression that the public is too ill-informed to understand them—that is, to understand their ordinarily somewhat technical method of expression. If, therefore, in the following pages I may sometimes seem to take more space and time for an explanation than appears necessary, I hope the student will overlook it, as I seek to be thoroughly understood. My hope with reference to this work is that it may prove of actual value to the earnest student in helping him reach the excellence which is the common aim of all true artists. ? ?J. A. Barhydt. About Author: To many who know nothing about the art of crayon portraiture, the mastery of it not only seems very difficult, but almost unattainable. In fact, any work of art of whatever description, which in its execution is beyond the knowledge or comprehension of the spectator, is to him a thing of almost supernatural character. Of course, this is more decided when the subject portrayed carries our thoughts beyond the realms of visible things. But the making of crayon portraits is not within the reach alone of the trained artist who follows it as a profession. I claim that any one who can learn to write can learn to draw, and that any one who can learn to draw can learn to make crayon portraits. Making them over a photograph, that is, an enlargement, is a comparatively simple matter, as it does not require as much knowledge of drawing as do free-hand crayons. But you must not suppose that, because the photographic enlargement gives you the drawing in line and an indistinct impression of the form in light and shade, you are not required to draw at all in making a crayon portrait over such an enlargement. Some knowledge of drawing is necessary, though not a perfect knowledge. Many people err in supposing that only the exceptionally skilled can produce the human features in life-like form upon the crayon paper. While recognizing great differences in natural aptitude for drawing in different persons, just as those who use the pen differ widely in their skill, some being able to write with almost mechanical perfection of form, I still hold that any one who is able to draw at all can succeed in producing creditable crayons.. J. A. Barhydt.

Az ?rd?g egyetlen barátja

¥57.47

When does life begin?... A well-known book says "forty". A well-known radio program says "eighty". Some folks say it's mental, others say it's physical. But take the strange case of Mel Carlson who gave a lot of thought to the matter. Mel felt as if he were floating on clouds in the deepest, most intense dark he had ever experienced. He tried opening his eyes but nothing happened, only a sharp pain. Little bits of memory flashed back and he tried to figure out what could have happened, where he was. The last thing he could remember was the little lab hidden back in the mountains in an old mine tunnel. Remote, but only an hour's drive from the city. What had he been doing? Oh yes, arguing with Neil again. He even recalled the exact words."Damn it, Mel," his partner had said. "We've gone about as far as possible working with animal brains. We've got to get a human one." "We can't," Mel had disagreed. "There'd be enough of an uproar if the papers got hold of what we've been doing with animals. If we did get someone in a hospital to agree to let us use his brain on death, they would close us up tighter than a drum.""But our lab's too well hidden, they'd never know." "It wouldn't work anyway. The brain might be damaged for lack of oxygen and all of our work would go for nothing. Worse, it might indicate failure where a fresh, healthy brain would mean success.""We'll never know unless we try," said Neil almost violently, dark eyes glittering. "Our funds aren't going to last forever."

Drakula

¥18.74

Hark! hark! the dogs bark,The beggars are coming to town;Some in rags and some in tags,And some in a silken gown.Some gave them white bread,And some gave them brown,And some gave them a good horse-whip,And sent them out of the town. Little Jack Horner sat in the corner,Eating a Christmas pie;He put in his thumb, and pulled out a plum,And said, oh! what a good boy am I.

Lumi paralele. O c?l?torie prin crea?ie, dimensiuni superioare ?i viitorul cosmo

¥90.84

Sir Peter Paul Rubens ( 28 June 1577 – 30 May 1640), was a Flemish Baroque painter, and a proponent of an extravagant Baroque style that emphasised movement, colour, and sensuality. He is well known for his Counter-Reformation altarpieces, portraits, landscapes, and history paintings of mythological and allegorical subjects.In addition to running a large studio in Antwerp that produced paintings popular with nobility and art collectors throughout Europe.. Early lifeRubens was born in the German city of Siegen, Westphalia to Jan Rubens and Maria Pypelincks. His father, a Calvinist, and mother fled Antwerp for Cologne in 1568, after increased religious turmoil and persecution of Protestants during the rule of the Spanish Netherlands by the Duke of Alba. Jan Rubens became the legal advisor (and lover) of Anna of Saxony, the second wife of William I of Orange, and settled at her court in Siegen in 1570; their daughter Christine was born in 1571. Following Jan Rubens's imprisonment for the affair, Peter Paul Rubens was born in 1577. The family returned to Cologne the next year. In 1589, two years after his father's death, Rubens moved with his mother Maria Pypelincks to Antwerp, where he was raised as a Catholic. Religion figured prominently in much of his work and Rubens later became one of the leading voices of the Catholic Counter-Reformation style of painting (he had said "My passion comes from the heavens, not from earthly musings").In Antwerp, Rubens received a humanist education, studying Latin and classical literature. By fourteen he began his artistic apprenticeship with Tobias Verhaeght. Subsequently, he studied under two of the city's leading painters of the time, the late Mannerist artists Adam van Noort and Otto van Veen. Much of his earliest training involved copying earlier artists' works, such as woodcuts by Hans Holbein the Younger and Marcantonio Raimondi's engravings after Raphael. Rubens completed his education in 1598, at which time he entered the Guild of St. Luke as an independent master. Italy (1600–1608)In 1600, Rubens travelled to Italy. He stopped first in Venice, where he saw paintings by Titian, Veronese, and Tintoretto, before settling in Mantua at the court of Duke Vincenzo I Gonzaga. The coloring and compositions of Veronese and Tintoretto had an immediate effect on Rubens's painting, and his later, mature style was profoundly influenced by Titian. With financial support from the Duke, Rubens travelled to Rome by way of Florence in 1601. Last decade (1630–1640)The Exchange of Princesses, from the Marie de' Medici Cycle. Louvre, ParisRubens's last decade was spent in and around Antwerp. Major works for foreign patrons still occupied him, such as the ceiling paintings for the Banqueting House at Inigo Jones's Palace of Whitehall, but he also explored more personal artistic directions.In 1630, four years after the death of his first wife, the 53-year-old painter married 16-year-old Hélène Fourment. Hélène inspired the voluptuous figures in many of his paintings from the 1630s, including The Feast of Venus (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), The Three Graces and The Judgment of Paris (both Prado, Madrid). In the latter painting, which was made for the Spanish court, the artist's young wife was recognized by viewers in the figure of Venus. In an intimate portrait of her, Hélène Fourment in a Fur Wrap, also known as Het Pelsken, Rubens's wife is even partially modelled after classical sculptures of the Venus Pudica, such as the Medici Venus. In 1635, Rubens bought an estate outside of Antwerp, the Steen, where he spent much of his time. Landscapes, such as his Ch?teau de Steen with Hunter (National Gallery, London) and Farmers Returning from the Fields (Pitti Gallery, Florence), reflect the more personal nature of many of his later works. He also drew upon the Netherlandish traditions of Pieter Bruegel the Elder for inspiration in later works like Flemish Kermis (c. 1630; Louvre, Paris).

Hallatlan kiváncsiság

¥8.67

In creating psychoanalysis, a clinical method for treating psychopathology through dialogue between a patient and a psychoanalyst, Freud developed therapeutic techniques such as the use of free association (in which patients report their thoughts without reservation and in whichever order they spontaneously occur) and discovered transference (the process in which patients displace on to their analysts feelings derived from their childhood attachments), establishing its central role in the analytic process. Freud’s redefinition of sexuality to include its infantile forms led him to formulate the Oedipus complex as the central tenet of psychoanalytical theory. His analysis of his own and his patients' dreams as wish-fulfillments provided him with models for the clinical analysis of symptom formation and the mechanisms of repression as well as for elaboration of his theory of the unconscious as an agency disruptive of conscious states of mind. Freud postulated the existence of libido, an energy with which mental processes and structures are invested and which generates erotic attachments, and a death drive, the source of repetition, hate, aggression and neurotic guilt. In his later work Freud drew on psychoanalytic theory to develop a wide-ranging interpretation and critique of religion and culture. Psychoanalysis remains influential within psychotherapy, within some areas of psychiatry, and across the humanities. As such it continues to generate extensive and highly contested debate with regard to its therapeutic efficacy, its scientific status and as to whether it advances or is detrimental to the feminist cause. Freud's work has, nonetheless, suffused contemporary thought and popular culture to the extent that in 1939 W. H. Auden wrote, in a poem dedicated to him: "to us he is no more a person / now but a whole climate of opinion / under whom we conduct our different lives". About Author: Sigmund Freud (Born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist who became known as the founding father of psychoanalysis. Freud qualified as a doctor of medicine at the University of Vienna in 1881, and then carried out research into cerebral palsy, aphasia and microscopic neuroanatomy at the Vienna General Hospital. He was appointed a university lecturer in neuropathology in 1885 and became a professor in 1902.

Assassin's Creed - Egység

¥71.29

This is the Illustrated version of the "A Journal of the Plague Year", A work that is often read as if it were non-fiction is his account of the Great Plague of London in 1665: A Journal of the Plague Year, a complex historical novel published in 1722. Bring out your dead! The ceaseless chant of doom echoed through a city of emptied streets and filled grave pits. For this was London in the year of 1665, the Year of the Great Plague....In 1721, when the Black Death again threatened the European Continent, Daniel Defoe wrote "A Journal of the Plague Year" to alert an indifferent populace to the horror that was almost upon them. Through the eyes of a saddler who had chosen to remain while multitudes fled, the master realist vividly depicted a plague-stricken city. He re-enacted the terror of a helpless people caught in a tragedy they could not comprehend: the weak preying on the dying, the strong administering to the sick, the sinful orgies of the cynical, the quiet faith of the pious. With dramatic insight he captured for all time the death throes of a great city. In this Illustrated book, Noted all of Defoe's pamphlet writing was political. One pamphlet (originally published anonymously) entitled "A True Relation of the Apparition of One Mrs. Veal the Next Day after her Death to One Mrs. Bargrave at Canterbury the 8th of September, 1705," deals with interaction between the spiritual realm and the physical realm. It was most likely written in support of Charles Drelincourt's The Christian Defense against the Fears of Death (1651). It describes Mrs. Bargrave's encounter with an old friend Mrs. Veal, after she had died. It is clear from this piece and other writings, that while the political portion of Defoe's life was fairly dominant, it was by no means the only aspect: "Wherever God erects a house of prayerthe Devil always builds a chapel there;And 't will be found, upon examination,the latter has the largest congregation."— Defoe's The True-Born Englishman, 1701 Copyright & Illustrated by e-Kitap Projesi ABOUT AUTHOR: Daniel Defoe ( 1660 – 1731), born Daniel Foe, was an English trader, writer, journalist, pamphleteer, and spy, now most famous for his novel Robinson Crusoe.

Vészmadarak

¥57.47

"BLEAK HOUSE" is a novel by Charles Dickens, published in 20 monthly instalments between March 1852 and September 1853. It is held to be one of Dickens's finest novels, containing one of the most vast, complex and engaging arrays of minor characters and sub-plots in his entire canon. The story is told partly by the novel's heroine, Esther Summerson, and partly by a mostly omniscient narrator. Memorable characters include the menacing lawyer Tulkinghorn, the friendly but depressive John Jarndyce, and the childish and disingenuous Harold Skimpole, as well as the likeable but imprudent Richard Carstone. At the novel's core is long-running litigation in England's Court of Chancery, Jarndyce v Jarndyce, which has far-reaching consequences for all involved. This case revolves around a testator who apparently made several wills. The litigation, which already has taken many years and consumed between 60,000 and 70,000 in court costs, is emblematic of the failure of Chancery. Though Chancery lawyers and judges criticised Dickens's portrait of Chancery as exaggerated and unmerited, his novel helped to spur an ongoing movement that culminated in the enactment of legal reform in the 1870s. In fact, Dickens was writing just as Chancery was reforming itself, with the Six Clerks and Masters mentioned in Chapter One abolished in 1842 and 1852 respectively: the need for further reform was being widely debated. These facts raise an issue as to when Bleak House is actually set. Technically it must be before 1842, and at least some of his readers at the time would have been aware of this. However, there is some question as to whether this timeframe is consistent with the themes of the novel. The English legal historian Sir William Holdsworth set the action in 1827. Characters in Bleak House: As usual, Dickens drew upon many real people and places but imaginatively transformed them in his novel. Hortense is based on the Swiss maid and murderess Maria Manning. The "telescopic philanthropist" Mrs Jellyby, who pursues distant projects at the expense of her duty to her own family, is a criticism of women activists like Caroline Chisholm. The "childlike" but ultimately amoral character Harold Skimpole is commonly regarded as a portrait of Leigh Hunt. "Dickens wrote in a letter of 25 September 1853, 'I suppose he is the most exact portrait that was ever painted in words! ... It is an absolute reproduction of a real man'; and a contemporary critic commented, 'I recognized Skimpole instantaneously; ... and so did every person whom I talked with about it who had ever had Leigh Hunt's acquaintance.'"[2] G. K. Chesterton suggested that Dickens "may never once have had the unfriendly thought, 'Suppose Hunt behaved like a rascal!'; he may have only had the fanciful thought, 'Suppose a rascal behaved like Hunt!'". Mr Jarndyce's friend Mr Boythorn is based on the writer Walter Savage Landor. The novel also includes one of the first detectives in English fiction, Inspector Bucket. This character is probably based on Inspector Charles Frederick Field of the then recently formed Detective Department at Scotland Yard. Dickens wrote several journalistic pieces about the Inspector and the work of the detectives in Household Words, his weekly periodical in which he also published articles attacking the Chancery system. The Jarndyce and Jarndyce case itself has reminded many readers of the thirty-year Chancery case over Charlotte Smith's father-in-law's will. Major characters: Esther Summerson – the heroine of the story, and one of its two narrators (Dickens's only female narrator), raised as an orphan because the identity of her parents is unknown. At first, it seems probable that her guardian, John Jarndyce, is her father because he provides for her. This, however, he disavows shortly after she comes to live under his roof.

Around the World in Eighty Days: Illustrated

¥8.09

“Ah there, girls! How are you?”—“GOD SPEED YOU” “Oh, Nathalie, I do believe there’s Grace Tyson in her new motor-car,” exclaimed Helen Dame, suddenly laying her hand on her companion’s arm as the two girls were about to cross Main Street, the wide, tree-lined thoroughfare of the old-fashioned town of Westport, Long Island.Nathalie Page halted, and, swinging about, peered intently at the brown-uniformed figure of a young girl seated at the steering-wheel of an automobile, which was speeding quickly towards them. Yes, it was Grace, who, in her sprightliest manner, her face aglow from the invigorating breezes of an April afternoon, called out, “Ah there, girls! How are you? Oh, my lucky star must have guided me, for I have something thrilling to tell you!” As she spoke the girl guided the car to the curb, and the next moment, with an airy spring, had landed on the ground at their side.With a sudden movement the uniformed figure clicked her heels together and bent stiffly forward as her arm swung up, while her forefinger grazed her forehead in a military salute. “I salute you, comrades,” she said with grave formality, “at your service as a member of the Motor Corps of America. “Yes, girls,” she shrilled joyously, forgetting her assumed r?le in her eagerness to tell her news, “I’m on the job, for I’m to see active service for the United States government. I’ve just returned from an infantry drill of the Motor Corps at Central Park, New York. “No, I’ll be honest,” she added laughingly, in answer to the look of amazed inquiry on the faces of her companions, “and ’fess’ that I didn’t have the pleasure of drilling in public, for I’m a raw recruit as yet. We recruits go through our manual of arms at one of the New York armories, drilled by a regular army sergeant. Oh, I’ve been in training some time, for you know I took out my chauffeur’s and mechanician’s State licenses last winter. LENA HALSEY:Author of “Blue Robin, the Girl Pioneer”and “America’s Daughter”

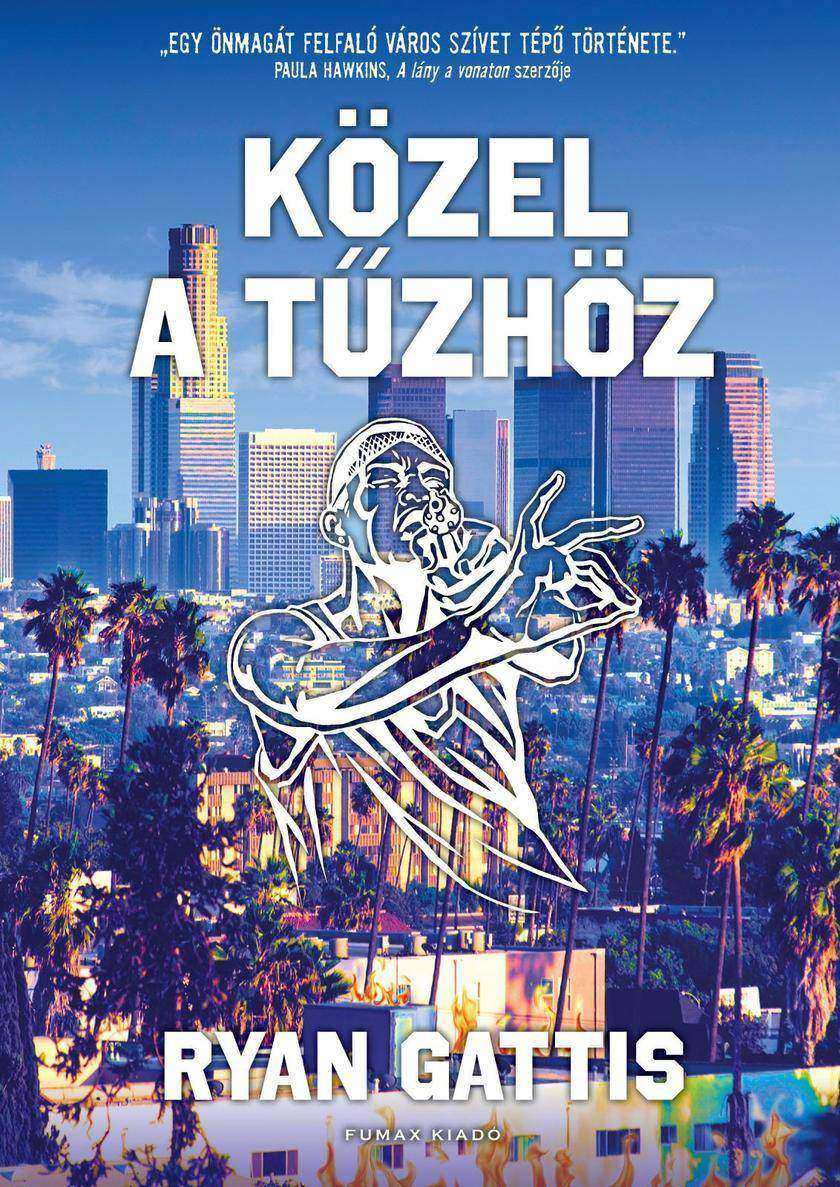

K?zel a t?zh?z

¥71.69

This book, in affectionate tribute to the gallant courage, rugged indepen-dence and wonderful endurance of those adventurous souls who formed the vanguard of civilization in the early history of the Territory of Arizona and the remainder of the Great West, is DEDICATED TO JOHN H. CADY and?BASIL D. WOON ?/ ?PATAGONIA, ARIZONA, NINETEEN-FIFTEEN. When I first broached the matter of writing his autobiography to John H. Cady, two things had struck me particularly. One was that of all the literature about Arizona there was little that attempted to give a straight, chronological and intimate description of events that occurred during the early life of the Territory, and, second, that of all the men I knew, Cady was best fitted, by reason of his extraordinary experiences, remarkable memory for names and dates, and seniority in pioneership, to supply the work that I felt lacking. Some years ago, when I first came West, I happened to be sitting on the observation platform of a train bound for the orange groves of Southern California. A lady with whom I had held some slight conversation on the journey turned to me after we had left Tucson and had started on the long and somewhat dreary journey across the desert that stretches from the "Old Pueblo" to "San Berdoo," and said: "Do you know, I actually used to believe all those stories about the 'wildness of the West.' I see how badly I was mistaken." She had taken a half-hour stroll about Tucson while the train changed crews and had been impressed by the—to the casual observer—sleepiness of the ancient town. She told me that never again would she look on a "wild West" moving picture without wanting to laugh. She would not believe that there had ever been a "wild West"—at least, not in Arizona. And yet it is history that the old Territory of Arizona in days gone by was the "wildest and woolliest" of all the West, as any old settler will testify.

购物车

购物车 个人中心

个人中心