人人都该懂的认识论

¥32.90

究竟什么才是知识? 知识从何而来? 为什么有些信念的来源就是可靠的知识? 哲学家对知识的思考有哪些不同的答案呢? …… 关于知识的问题,几千年来一直是哲学家思考的重,他们彼此争论,寻求问题的答案。对知识的哲学研究就是认识论。在书中,你可以读到柏拉图、康德、笛卡儿等不同哲学家对知识的思考,重塑你对知识的认识,也能在外在主义、内在主义、怀疑主义、经验主义的理解中启你对哲学的思考。 但你不要期待能在书中找到关于知识的*终答案,因为哲学中没有公认的答案。阅读本书时,*好的做法是试着自己评估每一种哲学立场,判断它是否正确。这不仅仅是一种本能反应,因为每一种立场都会伴随着赞成或反对的观,这些观都值得你自己去仔细考量,从而判断它们是否令人信服。你甚至可以添加一些自己的思考,享受一次令人兴奋的体验。 《人人都该懂的认识论》属于湛庐文化重磅推出的“新核心素养”系列图书之一。本系列图书致力于推广通识阅读,扩展读者的阅读面,培养批判性思考的能力。其中涵盖了哲学、心理学、法律、艺术、物理学、生物科技等诸多人文科学和自然科学的知识,其中《人人都该懂的认识论》从哲学的角度出发,对知识行了一场哲学思考,可以帮助你更好地理解知识,探讨知识到底从何而来,启一场对哲学的重新思考。

Пришестя робот?в.

¥31.07

"Wilde è profetico sin dalle prima righe, quando denuncia la prevalenza dell’emozione sulla razionalità, male principe del nostro tempo, e poi del pietismo sull’emancipazione, male di tanta politica di pseudo sinistra" (dall'Introduzione di Alfredo Sgarlato). Wilde: ?perché la vita raggiunga la sua più elevata perfezione, ci vuole qualche cosa di più. Ciò che ci vuole è l'individualismo?, ?Utopia? Una carta geografica del mondo in cui non sia segnato il paese dell'Utopia, non varrebbe la pena d'essere guardata, perché vi mancherebbe il paese in cui l'Umanità atterra ogni giorno. Ma non appena v'è sbarcata, ella guarda più lontano, scorge una terra ancora più bella, e spiega di nuovo le vele. Progredire significa realizzare l'Utopia?. SOMMARIO: Introduzione (di Alfredo Sgarlato) - Postfazione. Breve biblio-nota ai testi e alla traduzione (di Fabrizio Pinna) - OSCAR WILDE Società e libertà: elogio dell'individualismo - APPENDICE I Oscar Wilde, Rapporti fra il socialismo e l'individualismo (di Luigi Fabbri, 1913) - APPENDICE II The Soul of Man under Socialism (1891). LA COLLANA IN/DEFINIZIONI

Скоропадський. Спогади 1917-1918

¥22.74

Potere, cortigianeria, dispotismo, libertà, uguaglianza... attuali o inattuali la satira d'Holbach e La Boétie? Cambiano i tempi e i nomi, ma la natura umana nel suo fondo negli ultimi secoli non è mutata. Com'è virtù di tutti i classici, le loro voci continuano a farci sorridere, indignare e riflettere non solo sul passato ma ugualmente sul presente e sul futuro, su quanto in esso ci possa essere di desiderabile o indesiderabile. In Appendice, i testi si possono leggere anche nella loro originaria edizione in francese. SOMMARIO?- Fabrizio Pinna, Una introduzione (in due tempi) e qualche digressione: I. Barone d'Holbach, "Quest'arte sublime dello strisciare"...; II. ?tienne de La Boétie, "Siate determinati di non voler più servire ed eccovi liberi"... . LIBERT? & POTERE: Paul Henri Thiry d'Holbach, Saggio sull'arte di strisciare ad uso dei cortigiani; Paul Henri Thiry d'Holbach, I Cortigiani; Jean le Rond d'Alembert, Cortigiano; ?tienne de La Boétie, La servitù volontaria. APPENDICE I: Libertà Uguaglianza (1799)- Il Cittadino Editore. APPENDICE II: Essai sur l’art de ramper, à l’usage des courtisans (1764) - Paul Henri Thiry d'Holbach; Des Courtisans (1773) - Paul Henri Thiry d'Holbach; Courtisan (1752) / Courtisane (1754) - Jean le Rond d'Alembert; Discours de la servitude volontaire o Contr'un (1549) - ?tienne de La Boétie.?LE COLLANE IN/DEFINIZIONI & CON(TRO)TESTI

Ruins of Ancient Cities: (Volume -II)

¥28.61

More’s “Utopia” was written in Latin, and is in two parts, of which the second, describing the place ([Greek text]—or Nusquama, as he called it sometimes in his letters—“Nowhere”), was probably written towards the close of 1515; the first part, introductory, early in 1516. The book was first printed at Louvain, late in 1516, under the editorship of Erasmus, Peter Giles, and other of More’s friends in Flanders. It was then revised by More, and printed by Frobenius at Basle in November, 1518. It was reprinted at Paris and Vienna, but was not printed in England during More’s lifetime. Its first publication in this country was in the English translation, made in Edward’s VI.’s reign (1551) by Ralph Robinson. It was translated with more literary skill by Gilbert Burnet, in 1684, soon after he had conducted the defence of his friend Lord William Russell, attended his execution, vindicated his memory, and been spitefully deprived by James II. of his lectureship at St. Clement’s. Burnet was drawn to the translation of “Utopia” by the same sense of unreason in high places that caused More to write the book. Burnet’s is the translation given in this volume. The name of the book has given an adjective to our language—we call an impracticable scheme Utopian. Yet, under the veil of a playful fiction, the talk is intensely earnest, and abounds in practical suggestion. It is the work of a scholarly and witty Englishman, who attacks in his own way the chief political and social evils of his time. Beginning with fact, More tells how he was sent into Flanders with Cuthbert Tunstal, “whom the king’s majesty of late, to the great rejoicing of all men, did prefer to the office of Master of the Rolls;” how the commissioners of Charles met them at Bruges, and presently returned to Brussels for instructions; and how More then went to Antwerp, where he found a pleasure in the society of Peter Giles which soothed his desire to see again his wife and children, from whom he had been four months away. Then fact slides into fiction with the finding of Raphael Hythloday (whose name, made of two Greek words [Greek text] and [Greek text], means “knowing in trifles”), a man who had been with Amerigo Vespucci in the three last of the voyages to the new world lately discovered, of which the account had been first printed in 1507, only nine years before Utopia was written. Designedly fantastic in suggestion of details, “Utopia” is the work of a scholar who had read Plato’s “Republic,” and had his fancy quickened after reading Plutarch’s account of Spartan life under Lycurgus. Beneath the veil of an ideal communism, into which there has been worked some witty extravagance, there lies a noble English argument. Sometimes More puts the case as of France when he means England. Sometimes there is ironical praise of the good faith of Christian kings, saving the book from censure as a political attack on the policy of Henry VIII. Erasmus wrote to a friend in 1517 that he should send for More’s “Utopia,” if he had not read it, and “wished to see the true source of all political evils.” And to More Erasmus wrote of his book, “A burgomaster of Antwerp is so pleased with it that he knows it all by heart.” Sir Thomas More, son of Sir John More, a justice of the King’s Bench, was born in 1478, in Milk Street, in the city of London. After his earlier education at St. Anthony’s School, in Threadneedle Street, he was placed, as a boy, in the household of Cardinal John Morton, Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Chancellor. It was not unusual for persons of wealth or influence and sons of good families to be so established together in a relation of patron and client. The youth wore his patron’s livery, and added to his state. The patron used, afterwards, his wealth or influence in helping his young client forward in the world.

Nature

¥9.24

The Prince (Italian: Il Principe) is a political treatise by the Italian diplomat, historian and political theorist Niccolò Machiavelli. From correspondence a version appears to have been distributed in 1513, using a Latin title, De Principatibus (About Principalities). But the printed version was not published until 1532, five years after Machiavelli's death. This was done with the permission of the Medici pope Clement VII, but "long before then, in fact since the first appearance of the Prince in manuscript, controversy had swirled about his writings" Although it was written as if it were a traditional work in the Mirror of Princes style, it is generally agreed that it was especially innovative, and not only because it was written in Italian rather than Latin. The Prince is sometimes claimed to be one of the first works of modern philosophy, in which the effective truth is taken to be more important than any abstract ideal. It was also in direct conflict with the dominant Catholic and scholastic doctrines of the time concerning how to consider politics and ethics. Although it is relatively short, the treatise is the most remembered of his works and the one most responsible for bringing "Machiavellian" into wide usage as a pejorative term. It also helped make "Old Nick" an English term for the devil, and even contributed to the modern negative connotations of the words "politics" and "politician" in western countries. In terms of subject matter it overlaps with the much longer Discourses on Livy, which was written a few years later. In its use of examples who were politically active Italians who perpetrated criminal deeds for politics, another lesser-known work by Machiavelli which The Prince has been compared to is the Life of Castruccio Castracani. The descriptions within The Prince have the general theme of accepting that ends of princes, such as glory, and indeed survival, can justify the use of immoral means to achieve those ends.

Liberty Girl

¥19.05

Human reason, in one sphere of its cognition, is called upon to consider questions, which it cannot decline, as they are presented by its own nature, but which it cannot answer, as they transcend every faculty of the mind. It falls into this difficulty without any fault of its own. It begins with principles, which cannot be dispensed with in the field of experience, and the truth and sufficiency of which are, at the same time, insured by experience. With these principles it rises, in obedience to the laws of its own nature, to ever higher and more remote conditions. But it quickly discovers that, in this way, its labours must remain ever incomplete, because new questions never cease to present themselves; and thus it finds itself compelled to have recourse to principles which transcend the region of experience, while they are regarded by common sense without distrust. It thus falls into confusion and contradictions, from which it conjectures the presence of latent errors, which, however, it is unable to discover, because the principles it employs, transcending the limits of experience, cannot be tested by that criterion. The arena of these endless contests is called Metaphysic.Time was, when she was the queen of all the sciences; and, if we take the will for the deed, she certainly deserves, so far as regards the high importance of her object-matter, this title of honour. Now, it is the fashion of the time to heap contempt and scorn upon her; and the matron mourns, forlorn and forsaken, like Hecuba: At first, her gover Modo maxima rerum, Tot generis, natisque potens... Nunc trahor exul, inops. —Ovid, Metamorphoses. xiii under the administration of the dogmatists, was an absolute despotism. But, as the legislative continued to show traces of the ancient barbaric rule, her empire gradually broke up, and intestine wars introduced the reign of anarchy; while the sceptics, like nomadic tribes, who hate a permanent habitation and settled mode of living, attacked from time to time those who had organized themselves into civil communities. But their number was, very happily, small; and thus they could not entirely put a stop to the exertions of those who persisted in raising new edifices, although on no settled or uniform plan. In recent times the hope dawned upon us of seeing those disputes settled, and the legitimacy of her claims established by a kind of physiology of the human understanding—that of the celebrated Locke. But it was found that—although it was affirmed that this so-called queen could not refer her descent to any higher source than that of common experience, a circumstance which necessarily brought suspicion on her claims—as this genealogy was incorrect, she persisted in the advancement of her claims to sovereignty. Thus metaphysics necessarily fell back into the antiquated and rotten constitution of dogmatism, and again became obnoxious to the contempt from which efforts had been made to save it. At present, as all methods, according to the general persuasion, have been tried in vain, there reigns nought but weariness and complete indifferentism—the mother of chaos and night in the scientific world, but at the same time the source of, or at least the prelude to, the re-creation and reinstallation of a science, when it has fallen into confusion, obscurity, and disuse from ill directed effort. I do not mean by this a criticism of books and systems, but a critical inquiry into the faculty of reason, with reference to the cognitions to which it strives to attain without the aid of experience; in other words, the solution of the question regarding the possibility or impossibility of metaphysics, and the determination of the origin, as well as of the extent and limits of this science. All this must be done on the basis of principles. ABOUT AUTHOR: That all our knowledge begins with experience there can be no doubt. For how is it possible that the faculty of cognition should be awakened into exercise otherwise than by means of objects which affect our senses, and partly of themselves produce representations, partly rouse our powers of understanding into activity, to compare to connect, or to separate these, and so to convert the raw material of our sensuous impressions into a knowledge of objects, which is called experience? In respect of time, therefore, no knowledge of ours is antecedent to experience, but begins with it. But, though all our knowledge begins with experience, it by no means follows that all arises out of experience. For, on the contrary, it is quite possible that our empirical knowledge is a compound of that which we receive through impressions, and that which the faculty of cognition supplies from itself (sensuous impressions giving merely the occasion), an addition which we cannot distinguish from the original element given by sense, till long practice has made us attentive to, and skilful in separating it. It is, therefore, a question which requires close investigation, and not to b

The Sorrows of Young Werther

¥18.74

Among the notable books of later times-we may say, without exaggeration, of all time--must be reckoned The Confessions of Jean Jacques Rousseau. It deals with leading personages and transactions of a momentous epoch, when absolutism and feudalism were rallying for their last struggle against the modern spirit, chiefly represented by Voltaire, the Encyclopedists, and Rousseau himself--a struggle to which, after many fierce intestine quarrels and sanguinary wars throughout Europe and America, has succeeded the prevalence of those more tolerant and rational principles by which the statesmen of our own day are actuated. On these matters, however, it is not our province to enlarge; nor is it necessary to furnish any detailed account of our author's political, religious, and philosophic axioms and systems, his paradoxes and his errors in logic: these have been so long and so exhaustively disputed over by contending factions that little is left for even the most assiduous gleaner in the field. The inquirer will find, in Mr. John Money's excellent work, the opinions of Rousseau reviewed succinctly and impartially. The 'Contrat Social', the 'Lattres Ecrites de la Montagne', and other treatises that once aroused fierce controversy, may therefore be left in the repose to which they have long been consigned, so far as the mass of mankind is concerned, though they must always form part of the library of the politician and the historian. One prefers to turn to the man Rousseau as he paints himself in the remarkable work before us. That the task which he undertook in offering to show himself--as Persius puts it--'Intus et in cute', to posterity, exceeded his powers, is a trite criticism; like all human enterprises, his purpose was only imperfectly fulfilled; but this circumstance in no way lessens the attractive qualities of his book, not only for the student of history or psychology, but for the intelligent man of the world. Its startling frankness gives it a peculiar interest wanting in most other autobiographies. Many censors have elected to sit in judgment on the failings of this strangely constituted being, and some have pronounced upon him very severe sentences. Let it be said once for all that his faults and mistakes were generally due to causes over which he had but little control, such as a defective education, a too acute sensitiveness, which engendered suspicion of his fellows, irresolution, an overstrained sense of honour and independence, and an obstinate refusal to take advice from those who really wished to befriend him; nor should it be forgotten that he was afflicted during the greater part of his life with an incurable disease. Lord Byron had a soul near akin to Rousseau's, whose writings naturally made a deep impression on the poet's mind, and probably had an influence on his conduct and modes of thought: In some stanzas of 'Childe Harold' this sympathy is expressed with truth and power; especially is the weakness of the Swiss philosopher's character summed up in the following admirable lines: "Here the self-torturing sophist, wild Rousseau, The apostle of affliction, he who threw Enchantment over passion, and from woe Wrung overwhelming eloquence, first drew The breath which made him wretched; yet he knew How to make madness beautiful, and cast O'er erring deeds and thoughts a heavenly hue Of words, like sunbeams, dazzling as they passed The eyes, which o'er them shed tears feelingly and fast. "His life was one long war with self-sought foes, Or friends by him self-banished; for his mind Had grown Suspicion's sanctuary, and chose, For its own cruel sacrifice, the kind, 'Gainst whom he raged with fury strange and blind. But he was frenzied,-wherefore, who may know? Since cause might be which skill could never find; But he was frenzied by disease or woe To that worst pitch of all, which wears a reasoning show."

The Tragedy of Julius Caesar

¥18.74

Mülkiyet kar??t? ya?l? anar?ist, hayat?n?n son y?llar?nda ironik bir durumda kald?. ?svi?re vatanda?l???na girmenin yollar?n? arayan Bakunin'e sunulan se?enek, orada bir ev sahibi olmas?yd? ve belki de en hazini, sahip olaca?? bu ev nedeniyle, polisin, resm? tutanaklara “Michael Bakunin, rantiye” notunu dü?mesiydi. 18 May?s 1814'te Rusya'da do?an Michael Aleksandrovich Bakunin, 1 Temmuz 1876'da ?ldü?ünde ülkesinden ?ok uzaklardayd? ve cenazesinde yaln?zca 30–40 ki?i vard?. Gen? Bakunin i?in, “A?k, insan?n yeryüzündeki en üst misyonuydu. Bir insan?n kendini a?ks?z vermesi, Kutsal Ruh’a kar?? i?lenmi? bir günaht?”.. ?Kad?nlar taraf?ndan olduk?a ?ekici bulunan Mihail'in ise kad?nlarla ili?kisi hep ruhsal bir a?k olarak kald?.??svi?re'nin muhte?em manzaras? e?li?inde George Sand romanlar? okuyan Bakunin, Frans?z dü?üncesinin Alman dü?üncesinden üstün oldu?u inanc?n? sa?lamla?t?r?yordu. ? Bakunin, Marx i?in, “O, beni duygusal idealist olarak adland?r?yordu; hakl?yd?. Ben de onu, hoyrat, kendini be?enmi? ve ac?mas?z olarak de?erlendiriyordum; ben de hakl?yd?m” diyordu.. ? Kendisine ili?kin konularda kindar olmayan Bakunin, Herzen'in kar?s?na g?sterdi?i so?uklu?u hayat?n?n sonuna kadar unutamad?.?“Art?k reaksiyonun muzaffer gü?lerine kar?? Sisifos'un ta??n? yuvarlamak i?in ne gerekli güce ne de güvene sahibim. Bu yüzden, mücadeleden ?ekiliyor ve arkada?lar?mdan tek bir iyilik bekliyorum: "Unutulmak”,?Orta ve ge? on dokuzuncu yüzy?lda, radikal sol –yani, a?g?zlü kapitalizm ele?tirmenleri ve sanayi i??ilerinin ?zgürlü?ünün savunucular?– iki temel franksiyona ayr?l?yordu: Marksistler ve anar?istler. Kabaca s?ylemek gerekirse (ki bu son derece kar???k bir hik?yedir), kazanan Marksistler oldu ve yirminci yüzy?l?n tüm ba?ar?l? sol devrimleri –Rus, ?in ve Küba, ?rne?in– Marksist ilkelere ba?l?l?klar?n? ilan ettiler. ? Marksistler ile anar?istler aras?ndaki sava? bu noktada tarihsel bir meraktan ?te devam eden bir meseledir. Pi?man olmayan ya da ele?tirilmeyen tek ger?ek Marksist sol Kim Jong Il ve taraf etraftaki birka? entelektüel ve profes?rdür. Anar?izm ise uygulanabilir bir toplumsal hareket olarak ?kinci Dünya Sava??yla yava? yava? tükenmeye yüz tutmu?ken küreselle?me kar??t? hareket ve d?nemimizin di?er radikalizmleri i?inde yeniden dirilmeye ba?lam??t?r. ? Ne var ki, d?neminde –Marx’?n di?erleriyle aras?ndaki– bu sava? bir ?lüm kal?m meselesiydi ve Marksizm muhtemel kapitalizm kar??t? olarak ve yan? s?ra anar?izm kar??t? olarak tan?mlan?yordu. Asl?nda, Marx’?n yazarl??? anar?izme y?nelik sald?r?lar? a??s?ndan handiyse gülün? bir geni?li?e ula?m??t?r. Marx’?n Alman ?deolojisi kitab?n?n büyük b?lümü –yüzlerce sayfas?– bireyci/anar?ist Max Stirner’e y?nelik bir sald?r?dan ibarettir. Felsefenin Sefaleti Proudhon’a kar?? büyük?e bir fikir sava??d?r. Marx onca zaman ve enerjisini Bakunin’e sald?rmaya harcam??t?r: ?“dangalak!”?“canavar, et ve ya? y???n?,” “sap?k” vesaire: ?bu tabirler, has?mlar? s?z konusu oldu?unda Marx’?n bildik üslubudur: yazarl??? yar? bilimsel inceleme, yar? s?zlü tacizdir. Marx’?n, gerek kendi a?z?ndan gerekse de kimi s?zcülerini kullanarak ony?llar boyunca y?neltti?i ve muhtemelen di?erleri denli e?lenceli olmayan var olan su?lamas?, Bakunin’in bir muhbir oldu?u y?nündeydi ve Marx’?n bu ba?ar?l? sald?r?lar? nihayetinde Bakunin’in Enternasyonal ???i Z?mb?rt?s?ndan tasfiyesine yol a?t?.. ?

?tvenezer lándzsa: Anjouk - V. rész

¥75.54

"A megsemmisülés rejtélyes sz?vege egyszerre filozófiai traktátus, misztikus beavatás és poszthumán próza. A kortárs irodalomban egyre inkább feler?s?dik ez a nem-antropocentrikus hang, mely nem emberi sorsokat akar elbeszélni, hanem a nyelv és az ember k?z?s hiányt?rténetére mutat rá. ?Mennyien kapaszkodtak a létbe, mint egy végtelen fa t?rzsébe” - írja Horváth Márk és Lovász ?dám, hiszen az emberi állapot csak a társadalmi, nyelvi és metafizikai katasztrófa terében értelmezhet?. Apokaliptikus (neo)romantika és abszurd k?ltészet. Az utolsó ember kézik?nyve a túlélés lehetetlenségér?l."Nemes Z. Márió Az Idegenre hárult a sors ajándéka, hogy els?ként az utolsó emberek k?zu?l végignézze minden ku?ls?dleges k?telék pusztulását, és bizalmát lelkébe, s?t a lelkén is túlra helyezze, minden emberit maga m?g?tt hagyva. Minden ház gerendái k?z?tt barátságok és szerelmek jól táplált holttestei indultak oszlásnak, míg csak a csont fehérlett ki a vízb?l. Mint rég elhagyott kik?t?k tornyai, olyan hívogatóak voltak ezek a csontok az új kor embere számára.

The World Set Free

¥18.74

Kitab?n ba?l?ca vasf? olarak, Antik Yunan polisinden günümüze uzanan yolda, ?ocuk ve gen? yeti?tirmenin kamusal ve insan? ?nemini ortaya koyarken, fizik?, ahl?k? ve kültürel y?nleriyle bir bütün olarak e?itim felsefesi üzerine kaleme al?nm?? en temel eserlerden biri olmas? g?sterilebilir… ?Bu noktada, Rousseau’nun, “Tüm yazd?klar?m i?inde en iyi eserim” diye takdim etti?i?Emile’in 1762’de yay?nland???nda lanetlenip, 30 y?l sonra, Frans?z Devrimi’nin ?ncüleri i?in Frans?z milli e?itiminin ilham kayna?? addedildi?i dikkate al?nd???nda, Kant’?n e?itim üzerine sarf etti?i s?zlerin tarihsel ve toplumsal ba?lam? da ortaya ??kar. 18.yüzy?l?n ortalar?ndan 19.yüzy?l?n ba?lar?na dek ge?en bir ?mürlük sürede k?ta Avrupas? büyük bir do?umun sanc?lar?yla sars?lmaktad?r. ?ncesi ve sonras? diye tarihi ikiye ay?ran ?ifte Devrim (Sanayi ve Frans?z Devrimi) büyük bir zihinsel d?nü?üme yol a?mak üzeredir. Kant’? büyüten, ya da büyüklü?üne ayr?ca de?er katan bir unsur da, onun i?te bu ?a??n insan? olmas?d?r. ?Kant, 1806’daki Jena Sava??n? ve Napoleon i?galinin Alman milleti üzerinde yaratt??? ?ok ve deh?eti g?remeden vefat etse de, Wilhelm von Humboldt gibi e?itim reformcular? arac?l???yla Prusya (genel itibar?yla da Alman) e?itim sistemi i?in ne denli ?nemli bir yol a?t???n? tüm kitap boyunca seziyor gibidir. Bununla birlikte Kant’?nE?itim ?zerine’si, milli dilde ibadet edip, okumay? yazmay? te?vik eden Luhterci gelene?in Pietizmle kendini yenilemi? ve Büyük Frederich taraf?ndan te?vik edilmi? olan e?itim anlay???n?n olgunla?ma ?a??n?n da bir ürünüdür. Bu sebeple, kitab?n tamam?na h?kim olan motif, Ayd?nlanmac? bir “i?sel ?zgürle?im” ve “ruhan? terbiye” aras?nda kurulmas? gereken büyük dengedir. ? ? ?Bu arka plan? dikkate alarak, ?imdi kitaba biraz daha yak?ndan bakabiliriz… E?itim ?zerine, memleketin sayg?n ?evirmenlerinden biri olan Ahmet Aydo?an’?n sunu? ve ?ns?züyle ba?l?yor. ?stü kapal? fakat sitem dolu bir de?erlendirme yaz?s? olan “’Sapere Aude!’ Diye ??kt?k Yola”, Kant’a s?zü teslim etmeden evvel, 30 sayfada, Kant’?n dü?ünce dünyas?ndan ne denli uzakta kald???m?z?n ele?tirisini yap?yor. Bu arada, kitab?n ortaya ??k?? ?yküsüne de 22.sayfada a??klay?c? bir notla yer veriliyor. K?ningsberg ?niversitesi’nde muhtelif zamanlarda verilen dersler i?in haz?rlanan notlardan derlendi?i anla??lan?E?itim ?zerine, modern Türk?e’nin bir felsefe dili olamamas?n?n da etkisiyle, ?e?itli dipnotlar arac?l???yla kavramlar?n ve kelimelerin daha anla??l?r k?l?nd??? bir h?lde okura sunuluyor. ? “?nsan E?itilmesi Gereken Bir Varl?kt?r”: ? ?Kant, dü?üncelerini temellendirdi?i giri? sayfalar?nda insan?n e?itime muhta? ten varl?k oldu?u ger?e?inden hareket ediyor ve insan?n ancak e?itimle insan olabilece?ini dile getiriyor. (s.35) E?itime y?nelik bu yakla??m, Kant’?n idealizm felsefesinin ger?ekle?mesine giden yolu a?an anahtarlardan biri say?labilir.? ? ???NDEK?LER: ? KANT'IN YA?AMI…KANT'A G?RE AYDINLANMA NED?R?AHLAKIN METAF?Z???…KANT VE E??T?M ?ZER?NE….KANT VE TANRIKANT IN ELE?T?REL FELSEFES?KANT’IN ELE?T?REL FELSEFES?NE PLATON VE PARMEN?DES?N KATKILARI Kritisizm Nedir? KANT FELSEFES?N?N TEMEL KAVRAMLARIKANT’IN KURAMSAL METAF?Z?K ELE?T?R?S? HAKKINDAK? D???NCELER?..I. KANT'IN LE?BN?Z- WOLFF VE HUME'UN FELSEFELER?NE Y?NEL?K ELE?T?R?S?II. KANT'TA METAF?Z?K B?LG?N?N OLANA?I: METAF?Z?K OLANAKLI MIDIR?SONU?LARKANT’IN D?NYA YURTTA?LI?I AMACINA Y?NEL?K GENEL B?R TAR?H D???NCES?KANT’?I EBED? BARI?” D???NCES?S?YAS? HAKLARDA TEOR? VE PRAT?K ?L??K?S? ?ZER?NEK?RESELLE?EN SORUNLAR KAR?ISINDA KANT ET???UNUTULMAZ KANT S?ZLER?…..

A, mint alibi

¥66.79

Magyarázatok a Srimad-Bhagavatam tizedik éneke harminckettedik fejezetének 16-22. versáhez, az el?z? acaryák írásai alapján. A Na pāraye ’ham három része ?rī K???a, ?rī Caitanya Mahāprabhu és ?rīmatī Rādhārā?ī szeretetét mutatja be. Szeretetük egy-egy hatalmas folyóként h?mp?ly?g a prema óceánja felé. ?cāryáink kegyéb?l a bhakták megérinthetik ennek az óceánnak a partját, s néhány cseppnyi nektárt megízlelhetnek bel?le.

Heart of Darkness

¥9.07

The Republic (Greek: Politeia) is a Socratic dialogue, written by Plato around 380 BC, concerning the definition of (justice), the order and character of the just city-state and the just man, reason by which ancient readers used the name On Justice as an alternative title (not to be confused with the spurious dialogue also titled On Justice). The dramatic date of the dialogue has been much debated and though it must take place some time during the Peloponnesian War, "there would be jarring anachronisms if any of the candidate specific dates between 432 and 404 were assigned". It is Plato's best-known work and has proven to be one of the most intellectually and historically influential works of philosophy and political theory. In it, Socrates along with various Athenians and foreigners discuss the meaning of justice and examine whether or not the just man is happier than the unjust man by considering a series of different cities coming into existence "in speech", culminating in a city (Kallipolis) ruled by philosopher-kings; and by examining the nature of existing regimes. The participants also discuss the theory of forms, the immortality of the soul, and the roles of the philosopher and of poetry in society. Short Summary (Epilogue):X.1—X.8. 595a—608b. Rejection of Mimetic ArtX.9—X.11. 608c—612a. Immortality of the SoulX.12. 612a—613e. Rewards of Justice in LifeX.13—X.16. 613e—621d. Judgment of the Dead The paradigm of the city — the idea of the Good, the Agathon — has manifold historical embodiments, undertaken by those who have seen the Agathon, and are ordered via the vision. The centre piece of the Republic, Part II, nos. 2–3, discusses the rule of the philosopher, and the vision of the Agathon with the allegory of the cave, which is clarified in the theory of forms. The centre piece is preceded and followed by the discussion of the means that will secure a well-ordered polis (City). Part II, no. 1, concerns marriage, the community of people and goods for the Guardians, and the restraints on warfare among the Hellenes. It describes a partially communistic polis. Part II, no. 4, deals with the philosophical education of the rulers who will preserve the order and character of the city-state.In Part II, the Embodiment of the Idea, is preceded by the establishment of the economic and social orders of a polis (Part I), followed by an analysis (Part III) of the decline the order must traverse. The three parts compose the main body of the dialogues, with their discussions of the “paradigm”, its embodiment, its genesis, and its decline.The Introduction and the Conclusion are the frame for the body of the Republic. The discussion of right order is occasioned by the questions: “Is Justice better than Injustice?” and “Will an Unjust man fare better than a Just man?” The introductory question is balanced by the concluding answer: “Justice is preferable to Injustice”. In turn, the foregoing are framed with the Prologue (Book I) and the Epilogue (Book X). The prologue is a short dialogue about the common public doxai (opinions) about “Justice”. Based upon faith, and not reason, the Epilogue describes the new arts and the immortality of the soul. ? About Author: Plato (Greek: Platon, " 428/427 or 424/423 BC – 348/347 BC) was a philosopher in Classical Greece. He was also a mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Along with his mentor, Socrates, and his most-famous student, Aristotle, Plato helped to lay the foundations of Western philosophy and science. Alfred North Whitehead once noted: "the safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato." Plato's sophistication as a writer is evident in his Socratic dialogues; thirty-six dialogues and thirteen letters have been ascribed to him, although 15–18 of them have been contested. Plato's writings have been published in several fashions; this has led to several conventions regarding the naming and referencing of Plato's texts. Plato's dialogues have been used to teach a range of subjects, including philosophy, logic, ethics, rhetoric, religion and mathematics. Plato is one of the most important founding figures in Western philosophy. His writings related to the Theory of Forms, or Platonic ideals, are basis for Platonism. ? Early lifeThe exact time and place of Plato's birth are not known, but it is certain that he belonged to an aristocratic and influential family. Based on ancient sources, most modern scholars believe that he was born in Athens or Aegina between 429 and 423 BC. His father was Ariston. According to a disputed tradition, reported by Diogenes Laertius, Ariston traced his descent from the king of Athens, Codrus, and the king of Messenia, Melanthus. Plato's mother was Perictione, whose family boasted of a relationship with the famous Athenian lawmaker an

A leskel?d?

¥66.79

Within our Society (the International Society for Krishna Consciousness), guru has been taken to be synonymous with diksa-guru, but what about those great souls who have introduced us to Krsna consciousness? What relationship do we have with these Vaisnavas, and what are our obligations toward them, as well as toward parents, teachers, sannyasis, and other superiors who help guide us back to Godhead? Not much has been said by the Society on these topics, and hardly any appreciation is shown for those souls who labor to elevate us day by day.The scriptures, however, glorify as guru all Vaisnavas who guide a conditioned soul back to Godhead — be they instructors or initiators — advocating a culture of honor and respect. ISKCON needs to reflect upon these principles further, and the purpose of this book is to act as a catalyst toward such an end.

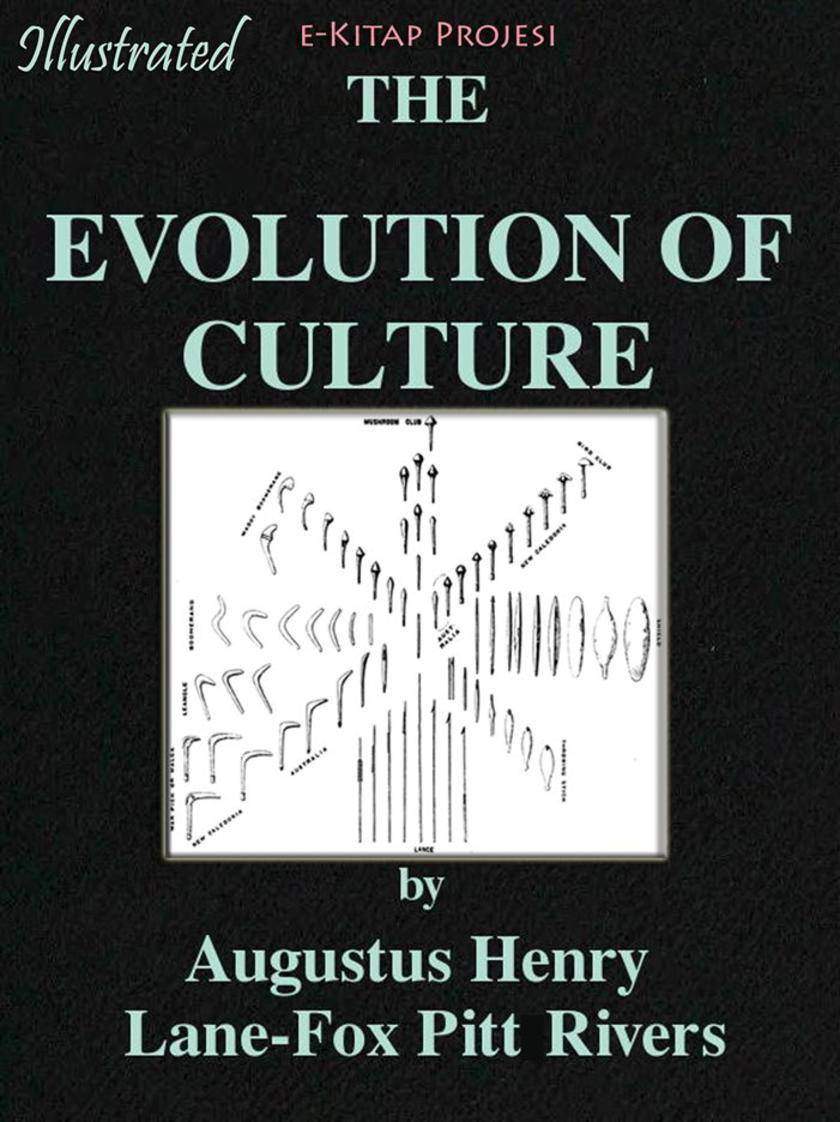

Evolution of the Culture

¥28.04

Paradise Lost is an epic poem in blank verse by the 17th-century English poet John Milton (1608–1674). The first version, published in 1667, consisted of ten books with over ten thousand lines of verse. A second edition followed in 1674, arranged into twelve books (in the manner of Virgil's Aeneid) with minor revisions throughout and a note on the versification. It is considered by critics to be Milton's "major work", and helped solidify his reputation as one of the greatest English poets of his time. The poem concerns the Biblical story of the Fall of Man: the temptation of Adam and Eve by the fallen angel Satan and their expulsion from the Garden of Eden. Milton's purpose, stated in Book I, is to "justify the ways of God to men" Short Summary:The poem is separated into twelve "books" or sections, the lengths of which vary greatly (the longest is Book IX, with 1,189 lines, and the shortest Book VII, with 640). The Arguments at the head of each book were added in subsequent imprints of the first edition. Originally published in ten books, a fully "Revised and Augmented" edition reorganized into twelve books was issued in 1674, and this is the edition generally used today. The poem follows the epic tradition of starting in medias res (Latin for in the midst of things), the background story being recounted later.Milton's story has two narrative arcs, one about Satan (Lucifer) and the other following Adam and Eve. It begins after Satan and the other rebel angels have been defeated and banished to Hell, or, as it is also called in the poem, Tartarus. In Pand?monium, Satan employs his rhetorical skill to organise his followers; he is aided by Mammon and Beelzebub. Belial and Moloch are also present. At the end of the debate, Satan volunteers to poison the newly created Earth and God's new and most favoured creation, Mankind. He braves the dangers of the Abyss alone in a manner reminiscent of Odysseus or Aeneas. After an arduous traversal of the Chaos outside Hell, he enters God's new material World, and later the Garden of Eden. At several points in the poem, an Angelic War over Heaven is recounted from different perspectives. Satan's rebellion follows the epic convention of large-scale warfare. The battles between the faithful angels and Satan's forces take place over three days. At the final battle, the Son of God single-handedly defeats the entire legion of angelic rebels and banishes them from Heaven. Following this purge, God creates the World, culminating in his creation of Adam and Eve. While God gave Adam and Eve total freedom and power to rule over all creation, He gave them one explicit command: not to eat from the Tree of the knowledge of good and evil on penalty of death.

MALARIA: История военного переводчика

¥11.77

A partir de uma sugest?o de Gilles Deleuze e Félix Guattari – a de que todos os filósofos ocidentais terminaram construindo, no interregno do seu pensamento, personagens conceituais, uma espécie de assinatura do filósofo – este livro objetiva identificar esse tra?o a partir da obra de Michel Foucault. A tese em quest?o é que este autor n?o se enquadra em uma imagem única, como a do Juiz em Kant, ou a do sedutor em Kierkegaard, mas em uma imagem híbrida e triádica, fazendo coro com muitos filósofos chamados de transversais e que se instalaram no horizonte de filosofias chamadas de pós-estruturalistas, como Deleuze.

Mindig is éjjel lesz

¥69.65

Sri Krsna számtalan univerzum vitathatatlan Ura, akit korlátlan er?, gazdagság, hírnév, tudás és lemondás jellemez, ám ezek az ?r?kké diadalmas energiák csupán részben tárják fel ?t. Végtelen dics?ségét csak az ismerheti meg, aki elb?v?l? szépségénél keres menedéket, ?sszes t?bbi fenséges tulajdonsága forrásánál, melynek páratlan transzcendentális teste ad otthont. Szépségének legf?bb jellemz?je az a mindenek f?l?tt álló édes íz, ami t?mény kivonata mindennek, ami édes. Minden édes dolgot túlszárnyal, és nem más, mint az édes íz megízlelésének képessége. Sri Krsna édes természete finom arany sugárzásként ragyog át transzcendentális testén. Govinda páratlanul gy?ny?r? testének legszebb és legédesebb része ragyogó arca. ?des hold-arcán rejtélyes mosolya a legédesebb, az az arcáról ragyogó ezüst holdsugár, ami nektárral árasztja el a világot. Mosolyának sugárzása nélkül keser? lenne a cukor, savanyú a méz, és a nektárnak sem lenne íze. Amikor mosolyának holdsugara elvegyül teste ragyogásával, a kett? együtt a kámfor aromájára emlékeztet. Ez a kámfor aztán ajkán keresztül a fuvolába kerül, ahonnan megfoghatatlan hangvibrációként t?r el?, és er?nek erejével rabul ejti azoknak az elméjét, akik hallják. Ahogy a szavak gondolatok mondanivalóját hordozzák, ahogy a gondolatok a szemben tükr?z?dnek, ahogy egy mosoly a szív érzelmeir?l árulkodik, úgy a fuvola hangja Sri Krsna szépségét viszi a fül?n keresztül a szív templomának oltárára.

Аnalyste

¥11.77

O que somos?De onde viemos?!Para onde vamos? A que caminhos a vida nos leva? Essas e outras quest?es aflitivas e de todos os tempos nos s?o solucionadas por León Denis neste opúsculo. Filho da dor, Denis sabe, como você também, o quanto viver, muitas vezes é sofrer. E por isso apresenta, de modo t?o leve a solu??o espírita, racional, para o problema do existir. Mais do que um livro de Filosofia espírita, você tem em m?os palavras de consolo e estímulo para que cada trope?o do caminho seja compreendido e por assim dizer, aproveitado! Venha acompanhar-nos nesta viagem e descubra, em rápidos parágrafos os porquês de sua vida, da nossa vida, do planeta, do Universo.? Aos poucos, entenderemos com a lógica espírita como tudo esta em seu devido lugar.

Безжальна правда про нещадний б?знес

¥24.53

Em Vida sem Princípio , Henry David Thoreau nos apresenta um verdadeiro manual de como viver em sociedade e em contato com a Natureza respeitando a natureza e ao próximo.? puro Transcendentalismo , um apelo para que cada um siga a sua própria luz interior.Este ensaio foi obtido a partir da palestra''What Shall It Profit? ''apresentada ao publico em 06 de dezembro de 1854, no Sal?o Railroad em Providence Rhode Island.Foi publicado pela primeira vez na edi??o de outubro de 1863 The Atlantic Monthly, onde foi dado o título moderno.Vida sem Princípio é um ensaio em que Thoreau coloca o seu programa para viver bem. Incluem-se aqui as suas ideias sobre a forma de abordagem da comunica??o interpessoal, modos de trabalho, sustento financeiro e outros códigos de conduta baseados na filosofia de de vida de Thoreau.'

Прода?ться все: Джефф Безос та ера Amazon

¥36.79

Dignità o miseria della natura umana? ?C'è un principio supposto prevalere tra molti che è del tutto incompatibile con ogni virtù o senso morale [...] Questo principio è che ogni benevolenza è mera ipocrisia, l'amicizia un inganno, lo spirito pubblico una farsa, la fedeltà un trucco per procurare fiducia e confidenza; e mentre tutti noi, in fondo, perseguiamo solo il nostro interesse privato, indossiamo questi bei travestimenti in modo da abbassare le difese degli altri ed esporli maggiormente alle nostre astuzie e macchinazioni?... Le meditazioni senza tempo di uno dei più grandi filosofi europei. SOMMARIO: Introduzione e avvertenza ai testi / Nota bibliografica: una mappa degli studi (di Fabrizio Pinna) - David Hume: Dignità o miseria della natura umana? / L'Amore di Sé. APPENDICE: Of the Dignity or Meanness of Human Nature; Of Self-love; My Own Life & Letter from Adam Smith, LL. D. to William Strahan, Esq.; Of the Reason of Animals; Of the Immortality of the Soul; Of Superstition and Enthusiasm; Of some Verbal Disputes. LE COLLANE IN/DEFINIZIONI & CON(TRO)TESTI

Перегляд позитивного мислення

¥16.35

A compreens?o de Contos d’Escárnio n?o poderia restringir-se à constru??o do horizonte no qual nasce, o século XX. A inten??o de escrever lixo e bestagem, anunciada pelo narrador, aos poucos, revela um grotesco vindo de um longínquo, de um aquém. Por isto, faz-se necessário também compreender o fluxo histórico-estético que encontra acolhida na imagina??o de Hilda Hilst, cujo amparo conceitual buscou-se à estética da recep??o e do efeito. Na Teoria Estética, o feio insurge como fen?meno da realidade artística contempor?nea; refúgio de sobrevivência da arte e dos belos escritos, deixa livre à plasticidade do presente a tarefa da denúncia da realidade. Em protesto, o dissonante reivindica cidadania e se mantém como possibilidade da arte. Neste sentido, tem lugar em Hilda Hilst a atualidade do grotesco.

Dream Psychology: Psychoanalysis the Dreams for Beginners

¥28.04

Ralph Waldo Emerson, was born at Boston in 1803 into a distinguished family of New England Unitarian ministers. His was the eighth generation to enter the ministry in a dynasty that reached back to the earliest days of Puritan America. Despite the death of his father when Emerson was only eleven, he was able to be educated at Boston Latin School and then Harvard, from which he graduated in 1821. After several years of reluctant school teaching, he returned to the Harvard Divinity School, entering the Unitarian ministry during a period of robust ecclesiastic debate. By 1829 Emerson was married and well on his way to a promising career in the church through his appointment to an important congregation in Boston. However, his career in the ministry did not last long. Following the death of his first wife, Ellen, his private religious doubts led him to announce his resignation to his congregation, claiming he was unable to preach a doctrine he no longer believed and that "to be a good minister it was necessary to leave the ministry."With the modest legacy left him from his first wife, Emerson was able to devote himself to study and travel. In Europe he met many of the important Romantic writers whose ideas on art, philosophy, and literature were transforming the writing of the Nineteenth Century. He also continued to explore his own ideas in a series of voluminous journals which he had kept from his earliest youth and from which virtually all of his literary creation would be generated. Taking up residence in Concord, Massachusetts, Emerson devoted himself to study, writing and a series of public lectures in the growing lyceum movement. From these lyceum addresses Emerson developed and then in 1836 published his most important work, Nature. Its publication also coincided with his organizing role in the Transcendental Club, a group of leading New England educators, clergy, and intellectuals interested in idealistic religion, philosophy, and literature.

购物车

购物车 个人中心

个人中心